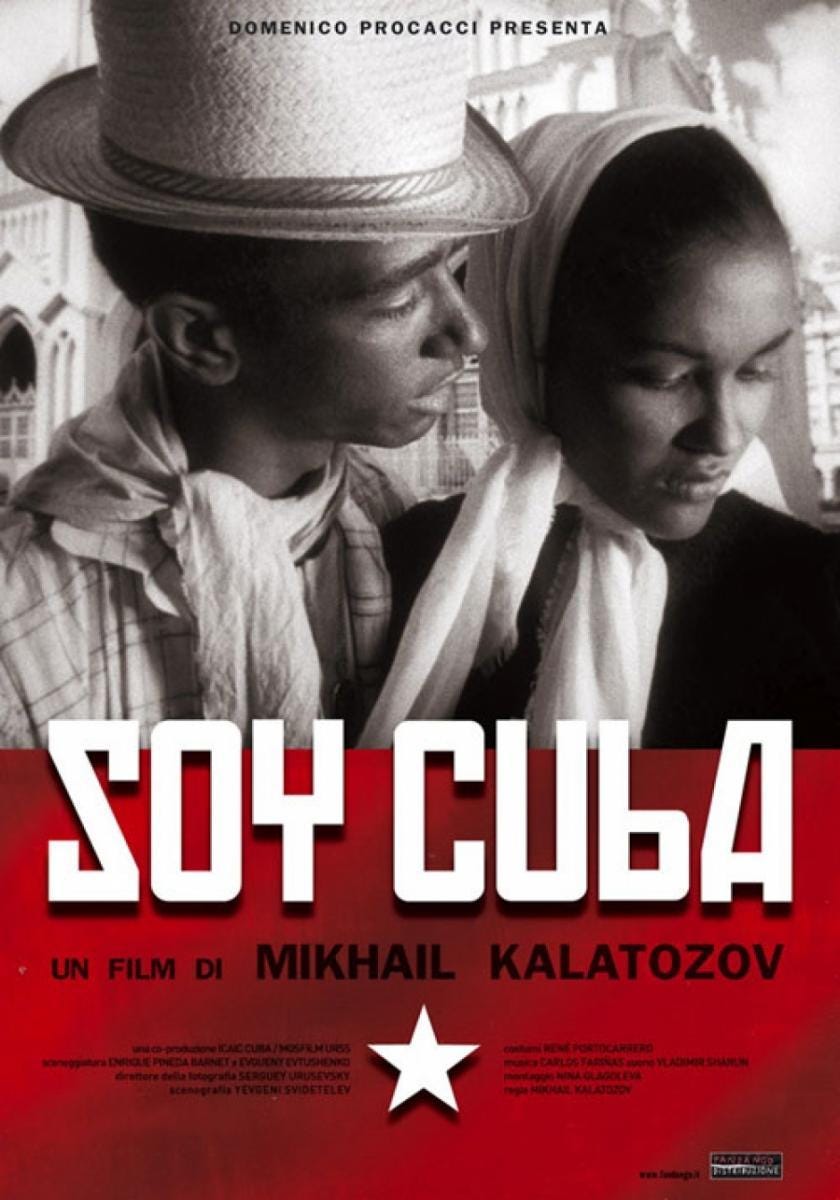

"Soy Cuba is one of the most visually hypnotic films ever made.

It's pure cinema." — Martin Scorsese

Visual storytelling playing a crucial role in filmmaking. A film's visual appeal, from its aesthetic to its composition and imagery, can captivate an audience. These visual elements not only engage viewers but also trigger an emotional connection, enhancing the overall impact of the film. The power of striking visuals can linger in the minds of the audience, resonating with them well beyond the initial viewing.

Three days after watching Soy Cuba (I Am Cuba), I’m still replaying the imagery in my head. And, wondering how this cinematic masterpiece was actually produced without modern technology.

With narration by Yevgeny Yevtushenko, a renowned Russian poet, novelist, and filmmaker celebrated for his contributions to post-Stalin Russian literature, the film is presented in a series of masterfully crafted single-take sequences, imparting a realistic drama-documentary effect.

In the opening scenes of "I Am Cuba," there's a remarkable shot that stands out as one of the most impressive in cinematic history, especially considering it was created in 1964, long before the advent of lightweight cameras and Steadicams. This makes the execution of the shot seem almost miraculous.

The scene is set on the rooftop deck of a luxurious hotel in Havana before the Castro era. Amidst a beauty pageant, the camera smoothly navigates through a crowd of bathing beauties. Then, in a breathtaking maneuver, it glides over the deck's edge and descends vertically, as if floating, down several stories to another deck adorned with a swimming pool. The camera continues its journey, elegantly approaching a bar and then trailing a waitress as she serves a drink to tourists. Remarkably, one of the tourists then stands and walks into the pool, with the camera seamlessly following her into the water, concluding the shot underwater.

This entire sequence appears to be captured in a single, unbroken take, a feat whose method of accomplishment remains a mystery. It's not just the technical brilliance that makes this shot noteworthy, but also its subtle reflection of the opulent life, 'la dolce vita,' a theme that intriguingly contrasts with the film's overall revolutionary and propagandistic tone.

The sequence begins at 2:09, contrasting with life in a poor Cuban village. The film is Spanish and Russian. There’s an icon to go full screen when you mouse over the top left corner of the video.

In a funeral scene, the camera tracks a flag-draped body on a stretcher through a thronged street, then ascends several floors, capturing the scene from above a building. Continuing without a break, it moves sideways into a cigar factory through a window and towards workers observing the procession from a rear window, then seems to glide out the window, floating above the street between buildings. These remarkable shots were achieved by the camera operator wearing a vest, akin to an early version of a Steadicam, equipped with hooks. A coordinated team of technicians attached and detached the operator’s vest to various pulleys and cables spanning across floors and rooftops

No dialogue here, what you see and hear tells the story. Words aren’t necessary. This is pure filmmaking and one of the great sequences of cinematography. Orson Welles’ film noir masterpiece, Touch of Evil opens with a three-minute, twenty-second tracking shot widely considered by critics as one of the greatest long takes in cinema history. And in Scorsese’s Goodfellas, there’s a steadycam shot where Henry Hill takes his date into the Copacabana that has achieved similar status.

In its stark technique and the raw beauty of its black-and-white shots, Soy Cuba stands as an undeniable classic. Director Mikhail Kalatozov captures the Cuba revolution's arc — from Batista's opulent Havana, the crushed tenant farmers, to the students' rising anger, and at last, Castro's troops emerging from the eastern mountains. The depiction of Americans in the film is humorous, presenting them as simplistic caricatures of sexist capitalists.

After a handful of screenings, the Russian-Cuban co-production was removed from circulation and put in a vault for thirty years. Although originally produced as propaganda to enhance Cuba's reputation during the Cold War, it failed to resonate with audiences in both Cuba and Russia. With a raging Cold War, the film was never shown in the United States.

Kalatozov, who earned widespread international acclaim for The Cranes Are Flying" in 1957, was known for his rather gymnastic camera techniques. He passed away in 1973, leaving his then-unknown masterpiece dormant until twenty years later, when Martin Scorsese and Francis Coppola, having learned about the film, played a pivotal role in its revival. Their efforts led to "Soy Cuba's" release in the United States in 1994.

The film naturally shows its age in terms of political context. Its portrayal of excesses and stereotypical 'imperialist Yankee' actions now comes across as somewhat old-fashioned. However, its status as a masterful example of black and white cinematography remains undiminished. For those watching it, one intriguing aspect to ponder is the technical wizardry behind how the camera seemingly floated down the wall in that remarkable shot.

Accordingly, Soy Cuba stands as a technical marvel in the realm of cinema. Its extensive takes and exceptional cinematography are so impressive Martin Scorsese remarked that had he seen it as a young director, his own directorial style would have been significantly different.

The film's political significance cannot be overstated, particularly considering Kalatozov's presence in Cuba during the peak of the Cold War and the Cuban Missile Crisis. His declaration to create a film in Cuba as a response to the naval blockade and "cruel aggression of American imperialism" underscores the movie's historical context. Soy Cuba has undoubtedly inspired numerous directors and artists and will continue to do so, regardless of its underlying communist propaganda themes.

Here’s the whole film with English subtitles.