A few months ago, I found myself in a dimly lit room in Guatemala, where a Spanish-dubbed version of Citizen Kane was playing on some off-brand Turner Classic Movies channel. There it was—Orson Welles’ magnum opus, with Charles Foster Kane lamenting his lost childhood in perfectly rolled R’s and lilting vowels. I was immediately hooked. My Spanish is good enough to order tacos al pastor and hold a basic conversation, but for Citizen Kane, I didn’t need subtitles. I’ve seen the damn thing so many times I could practically lip-sync the lines.

The first time I saw it, I was a wide-eyed teenager, freshly smitten with the idea of becoming a filmmaker. Later, at NYU Film School, Citizen Kane became a rite of passage—a film we studied not just to watch but to dissect. It was cinema school gospel, the film that every aspiring director had to genuflect before. Over the years, I’ve returned to it sporadically, but this time in Guatemala, a decade since I was it last, it hit me like a slap across the face.

Sitting in that room, as the flickering black-and-white images unfolded on a modest screen, it was like reuniting with an old friend. Not the kind of friend who overstays their welcome or makes the same tired jokes, but the kind who surprises you, deepens the conversation, and reminds you why you connected in the first place. And yeah, by the end—Rosebud—I was wiping away tears. Eighty years later, Citizen Kane still guts me.

The Writing: A Narrative Bombshell

What makes Citizen Kane legendary? For starters, it’s the script. Orson Welles and Herman J. Mankiewicz didn’t just write a screenplay—they detonated a narrative bomb. The movie unfolds in a fragmented, nonlinear structure, jumping between flashbacks, interviews, and perspectives. It opens with Kane’s death—Rosebud—and spirals into a journalistic treasure hunt to decode the cryptic last word.

In 1941, this was revolutionary. While most films in the studio system spoon-fed audiences a tidy beginning, middle, and end, Citizen Kane demanded that you put the pieces together yourself. It was storytelling as a puzzle box. Each flashback added a layer, a perspective, a bias. Was Kane a power-hungry megalomaniac or a misunderstood idealist? The film didn’t tell you what to think; it let you marinate in the ambiguity.

And the themes? Forget about it. Power, ambition, love, and loss. It’s Shakespearean in its sweep, with Kane’s unquenchable thirst for more—more newspapers, more statues, more adoration—leading to his ultimate ruin. And then there’s Rosebud, the ultimate cinematic gut-punch. Is it about innocence? Regret? The futility of life? Welles, ever the genius, leaves it just ambiguous enough to drive audiences into existential spirals.

Cinematography: A Visual Symphony

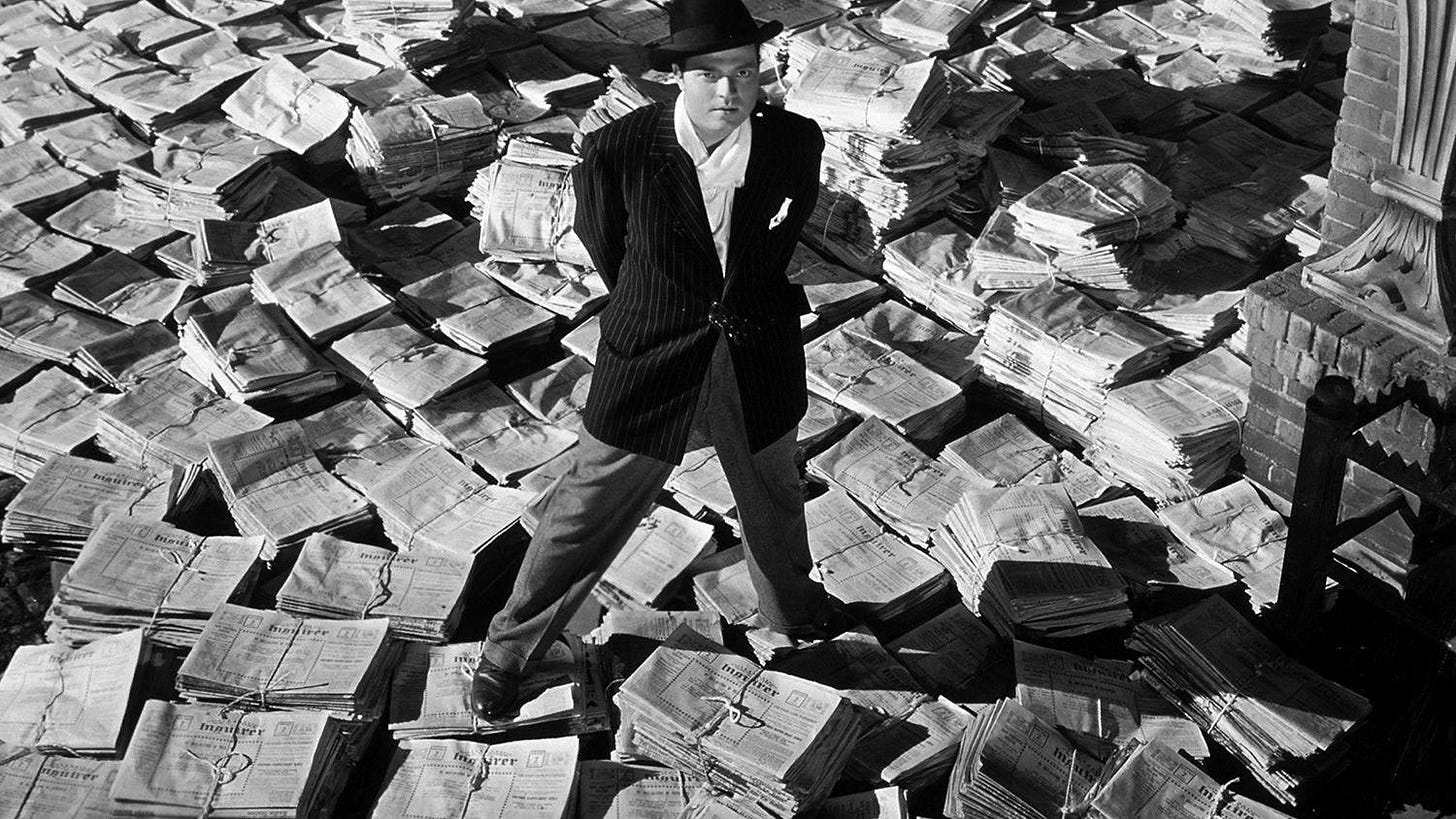

If the writing is the backbone of Citizen Kane, the cinematography is its beating heart. Gregg Toland, the genius director of photography, didn’t just point a camera—he reinvented what cameras could do. Deep focus photography, dramatic lighting, and insane camera angles turned every frame into a painting.

Take the deep focus. Everything from the foreground to the background is crystal clear, letting you absorb multiple layers of meaning in a single shot. Remember the scene where young Kane plays in the snow while his fate is sealed inside a distant room? That’s not just cinematography; that’s storytelling on steroids.

And the lighting? Holy hell. Inspired by German Expressionism, Welles and Toland drenched the film in shadows, making Kane’s life feel like one long, dark night of the soul. His rise to power? Flooded with light. His descent into despair? Consumed by shadows. It’s visual poetry, and it hits you in the gut every time.

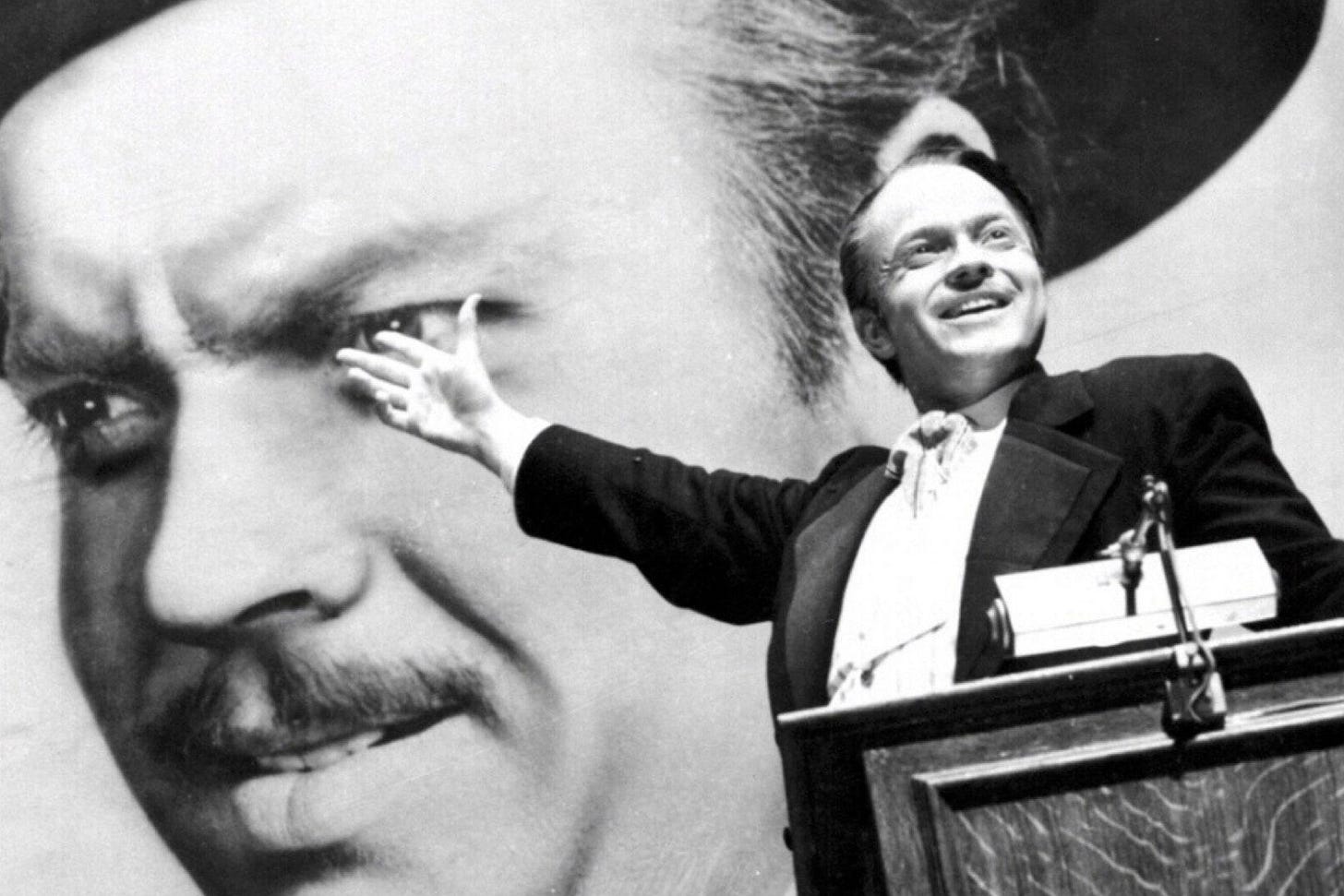

Then there are the angles—oh, the angles. Welles wasn’t content with eye-level shots; he wanted the camera to crawl, soar, and dive. Low angles make Kane look godlike in his arrogance, while high angles shrink him into insignificance as his empire crumbles. And let’s not forget the tracking shots, like the one that glides through the neon sign into the nightclub. That’s a masterclass in cinematic swagger. Before Kane, this sort of cinematography just didn’t exist.

Acting: The Towering Presence of Welles

Orson Welles was 25 when he made Citizen Kane. Twenty. Five. Most of us are barely functioning adults at that age, and this guy was starring in, directing, co-writing, and co-producing what would become the most iconic film in history.

His performance as Charles Foster Kane is nothing short of legendary. Welles captures every phase of Kane’s life—from the cocky young newspaper mogul to the bitter, broken recluse—with an authenticity that’s staggering. You believe him at every age, every stage.

Then there’s the supporting cast, plucked from Welles’ Mercury Theatre. Joseph Cotten as Jedediah Leland is the perfect foil to Kane’s bluster, bringing warmth and quiet dignity to the role. Dorothy Comingore as Susan Alexander is heartbreakingly raw, her breakdowns as harrowing as they are human. Even Everett Sloane as Mr. Bernstein, with his wistful memories of a girl on a ferry, leaves an indelible mark.

Why It Still Slaps

So, why does Citizen Kane still reign supreme more than eight decades later? Because it’s not just a movie—it’s an experience, a mirror held up to the human condition. It’s about ambition and failure, love and loneliness, the hunger for more, and the price of getting it. It doesn’t just entertain; it challenges you. It makes you think, feel, and, if you’re not careful, cry.

And technically? It’s still a gold standard. Every filmmaker worth their salt has borrowed from Welles and Toland, whether they know it or not. Nonlinear narratives? Thank Citizen Kane. Visual storytelling? Thank Citizen Kane. Hell, even the audacity to make a film about big ideas? Thank Citizen Kane.

In a world drowning in superhero flicks and algorithm-driven content, Citizen Kane stands tall, a reminder of what cinema can be when it aims for the stars. So, if you haven’t seen it—or haven’t revisited it in a while—do yourself a favor. Watch it. Let it wash over you. And when the credits roll, sit in the silence and let it sink in.

Because Citizen Kane isn’t just a movie. It’s the movie. And it always will be.

Following his sensational War of the Worlds radio broadcast, which became an international phenomenon, RKO handed Orson Welles the keys to the castle for Citizen Kane, granting him total creative control—a unicorn-level deal in Hollywood. But then William Randolph Hearst, catching the scent of what he thought was his own dirty laundry airing on the silver screen, threw the full weight of his newspaper empire into killing it. And kill it he did, at least commercially. Kane, the golden child of cinematic innovation, was buried alive by Hearst’s vendetta.

Welles’ follow-up, The Magnificent Ambersons, started with him holding the reins, but by the time it limped into theaters, the studio had hacked it to bits. What should have been another masterpiece became a cautionary tale for directors about the power of studio suits. That gutting marked the beginning of Welles’ stormy, self-destructive romance with Hollywood—a love-hate saga that makes Gone with the Wind look small.

In total, Welles directed seven studio films. From my vantage point, only one of those deserves the full spotlight treatment: Touch of Evil, a noir fever dream that redefined the genre. The rest of his studio output, while ambitious, was kneecapped by meddling producers, budget cuts, or both. It’s like handing Da Vinci a crayon and telling him to draw the Mona Lisa.

Then there’s the other Welles—the guerrilla filmmaker, scraping together budgets, shooting in far-flung locations, and funding projects by moonlighting in commercials and odd jobs.

Orson Welles became a prominent figure in the world of commercials later in his career, particularly in the 1970s and 1980s, as his fame and distinctive voice made him a sought-after spokesperson. While these commercials weren’t necessarily the source of his fame—he was already a cultural icon due to his work in radio, film, and theater—they helped cement his status as a pop culture legend.

He also crafted seven independent films, from Othello to F for Fake, that are pure, unfiltered Welles. Sure, some are uneven, but they crackle with the raw, untamed brilliance that defined his artistry. These films, often pieced together over years of scrappy, desperate financing, may have their flaws, but they remain unmistakably the work of a genius refusing to bow to convention.

In his later years, while Spielberg and the New Hollywood crowd worshipped at his altar, Welles couldn’t scrounge up the cash to make another feature. The irony is Shakespearean: the man who redefined the medium couldn’t find a dime in a town drowning in box office gold. His final opus, The Other Side of the Wind, a meta-commentary on the very system that crushed him, languished in limbo for decades. It took Netflix—a tech giant, not a studio—to resurrect and complete the film in 2018, long after Welles had shuffled off this mortal coil.

It’s a poetic ending, really. Welles, the perpetual outsider, finally gets his last word thanks to a new breed of media moguls. It’s a testament to his enduring legacy: you can bury the man, but his work? That’s forever.

Here’s the original trailer for Citizen Kane, produced by Welles himself.

Listen to the Deep Dive Podcast discuss the film.

Orson Welles, age 24, in September 1939. Just one year later, Welles would be directing, co-writing, and starring in Citizen Kane.

Citizen Kane may have found its moment again, given the relevance of its cautionary tale to our present political and media landscape. Thank you for a great tribute to the greatest cinematic masterpiece ever.

Wonderful piece.

The movie's so good that you can be forgiven for not mentioning Bernard Herrmann, who's score for "Kane" was nominated for an Academy Award but LOST TO HIMSELF! see below

Bernard Herrmann was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Score of a Dramatic Picture for his work on Citizen Kane (1941). He lost the award to All That Money Can Buy (also known as The Devil and Daniel Webster), for which he won the Oscar in 1942.

Herrmann's score for Citizen Kane is considered groundbreaking for its instrumentation and use of aural techniques. He used a variety of instruments, including organs, pianos, harps, horns, trumpets, tubas, and percussion. He also used electric instruments like the guitar, cello, and bass, and was the first to use an electric violin in a film. Herrmann also used two theremins, one for high pitches and one for low.

Herrmann also composed the score for Orson Welles's The Magnificent Ambersons (1942).