After the '70s, America changed. The spirit that drove us, that gathered us in churches and bars and on street corners, began to fade. We tried to pause, but instead got stuck. Clubs and gatherings, from reading groups to bowling alleys, began to decline. Our tradition of community, of coming together, seemed to struggle, caught in a decline. The activities that held us together started to come apart.

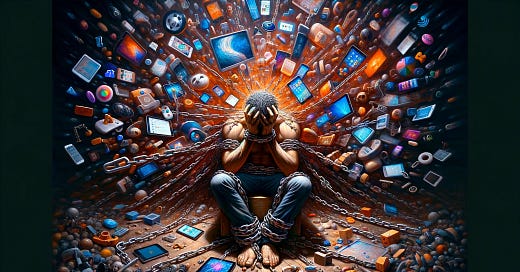

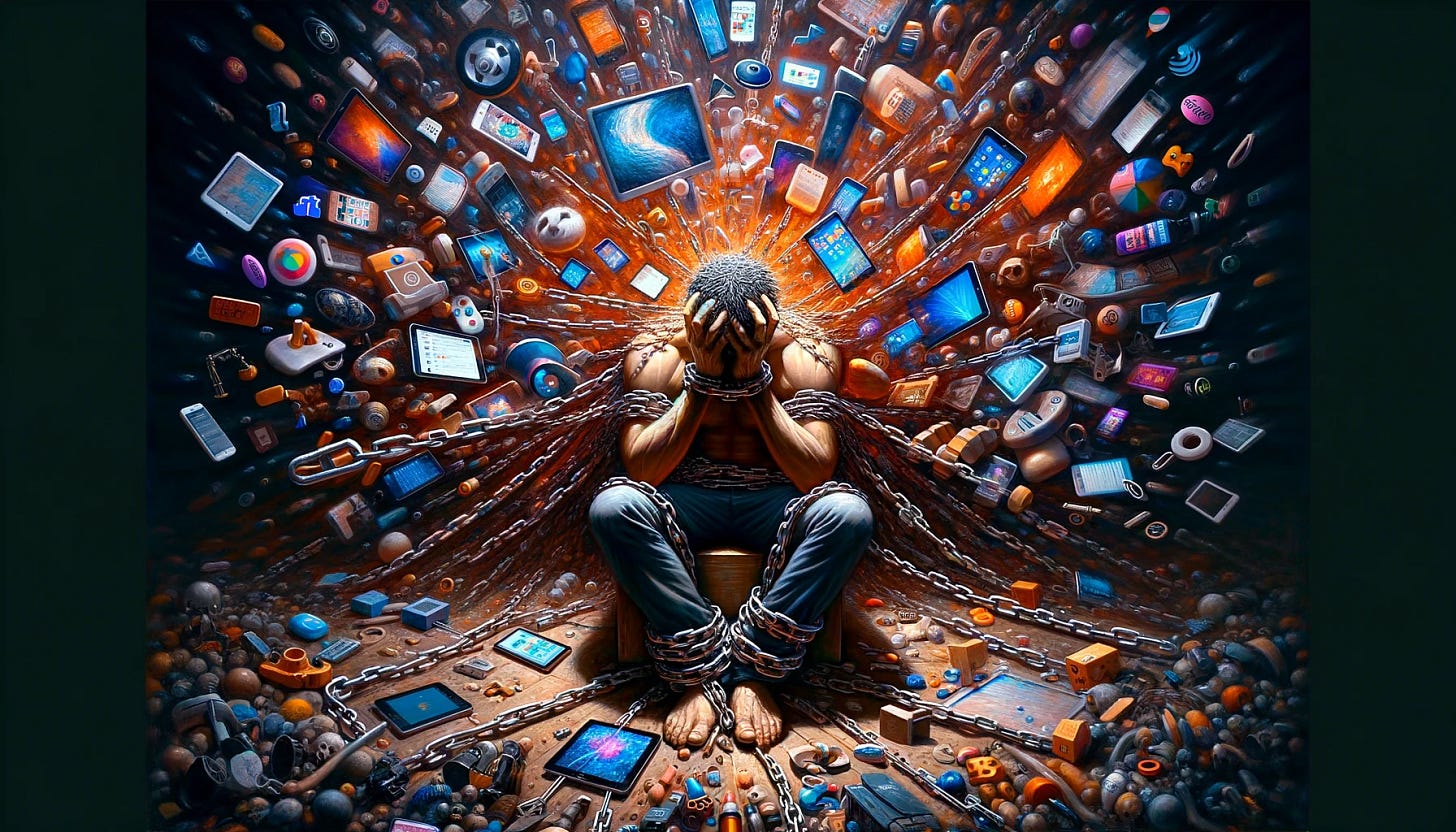

When smart phones and social media arrived in 2007, Americans stopped talking face-to-face. Singles, free from marriage, withdrew even more, into deeper isolation. Teenagers, lost online and stuck alone in dark rooms, saw their real friendships fade, their circles tighten and their laughter become rare in common spaces. With Uber Eats and Door Dash, we even stopped going out for food. And of course Amazon easily met the rest of our needs.

Today, many malls stand empty, marking a significant shift in the American narrative. We find ourselves in an era characterized by profound isolation, a time when our collective spirit experiences unprecedented solitude. This period sees the American spirit deeply immersed in its own solitude. Moreover, the divisive politics that now plague what was once a bastion of democracy only exacerbate the situation.

"So what?" one might ask. Being alone isn't the same as being lonely. Solitude has changed, becoming less lonely in itself. With endless calls, texts, emails, work talk, messages, and social posts, we're creating a thick web of online interaction, a vast sea of digital talk.

Why is Being Alone So Frightening?

Yet for Americans in the 2020s, solitude walks hand in hand with anxiety and discontent. Surveys show a harsh reality, especially the young who are caught in deep existential worry, facing personal and national futures with unprecedented dread. Teenage despair grows, setting records of hopelessness. Fewer young people have a close friend. This widespread unease about the country's state is growing.

In the early years of the new millenium, Americans have unknowingly joined a vast social experiment, cutting ourselves off from the tangible world's warmth. We've chosen to dive into isolation, captivated by screen light. Through these digital panes, we watch others live out the physical connections we've left behind. It's a strange path we've taken. The results, hardly pleasant, paint a picture of a society withdrawing into solitude, intriguing yet saddening.

The simple truth is that Americans are dialing down the time spent in the company of others in favor of increasing screen time, glued to their televisions and smartphones that offer unlimited content. Our youth in particular are swapping out real-life interactions for digital engagement.

Everyone's too busy. People in their 30s and 40s now have less free time than those twenty years ago. Americans like to spread out, and the way the housing market is set up, people often move away from their friends. With each move, they unknowingly buy a bit of loneliness with their new house.

With America's fading sense of unity, isolation stands out sharply. The wise and the tired have told me that being part of a community means just showing up. But where can we show up now? Church pews are emptying. Community centers and youth sports fields are quiet. Most bowling alleys and drive-ins have closed. Movie theaters are largely empty, except for the occasional blockbuster. Even offices, those places of accidental friendship, have given way to the charm of working from home. America is losing its communal rituals, choosing instead a mix of individual pleasures and the quiet pull of online isolation.

Combine these elements, and we see a society facing a deep social downturn, a time when the allure of screens overwhelms the need for human touch. For young people, this isn't just a broad social issue; it's a direct route to profound despair. Teenage loneliness isn't merely growing; it's soaring, alongside a surge in despair, depression, and a stark rise in thoughts of suicide. The CDC's Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance reveals the harsh reality: the share of teenage girls experiencing "persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness" jumped from 36% to 57% in ten years, and suicidal thoughts increased by 50%. We're navigating unknown territory, with no past experiences to help us steer through this tempest of social disengagement and mental health emergencies.

We're in a battle, pulled toward a loneliness we're not built for. Sartre said hell was other people. Perhaps he was right. Walking through this desert of solitude, we face something much worse.

We Are Really Never Alone

My baby boomer associates and I, we belong to a unique generation, straddling the line between a pre-internet existence and today's hyper-connected reality. Our childhoods were distinctively characterized by intervals of boredom, compelling us to stretch our imaginations and inventiveness to find amusement. This necessity to actively engage our creativity and expend significant energy to fill our time was nothing short of remarkable.

Contrast this with the experience of contemporary children. For them, the challenge is not finding ways to entertain themselves but rather the struggle to resist the constant barrage of distractions. They must make a concerted effort to experience boredom or quietude, a shift in human experience that cannot be overstated in its significance. This change raises critical questions about the future impact on humanity and the development of individuals raised in such an environment. How will a person shaped by these conditions differ in their adult years, three or four decades from now? It suggests the emergence of a fundamentally different type of human being.

The real predicament we face today is a crisis of presence. The profound shift from a world where boredom spurred creativity to one where constant stimulation is the norm, and this marks a significant transformation in the human condition.

Our trouble now is being truly present. With digital life, we're never alone, struggling to find quiet. People regularly hold their phones and check their emails or text or news or something else seemingly every 10 or 15 minutes. Unless we’re connected, we do not feel alive. Just being able to sit with ourselves is frightening for so many. We've moved from boredom driving creativity to constant noise, changing what it means to be human in ways we don't yet fully grasp. And this whole selfie thing, holy cow; we must post seemingly every facet of life, just to validate it.

Be Here Now

One answer is mindfulness, the practice of being fully present and engaged in the moment, aware of your thoughts, emotions, and sensations without judgment. It involves paying attention to our thoughts and feelings without getting caught up in them. This practice, rooted in Buddhist meditation, has been adopted widely in psychology and wellness fields to help reduce stress, improve mental health, and enhance overall well-being. Mindfulness can be practiced through meditation, but it also extends to daily activities, such as eating, walking, or listening, encouraging individuals to observe the present experience with acceptance and curiosity. Essentially, be here now as a wise man named Ram Das told us.

But realistically, in a world filled with increasing distractions and the lure of instant gratification, how many can actually shift to a different way of thinking and living—one where solitude and quietness are sources of peace of mind.

Community Matters

In May of 2022, I made the move from the US to Guanajuato, Mexico, and have since been thoroughly enjoying my life here, surrounded by a vibrant mix of locals and expatriates. My previous two decades were spent in Tucson, Arizona, a period marked by a sense of isolation. My interactions with neighbors were limited to brief exchanges of waves as they drove by, with any semblance of community disappearing behind the automatic closure of garage doors.

The political climate in Tucson grew increasingly toxic over the years, complicating communication and fostering an environment where I encountered anti-Semitism and a general air of indifference and suspicion from others.

Contrastingly, my experience in Mexico has been refreshingly different. Now a temporary resident, I find the communal atmosphere in this Central Highlands city to be welcoming. Casual strolls often lead to encounters with friends, and these meetings frequently evolve into meaningful conversations. Friendships are forged with ease, a stark difference from my time in Tucson. Despite economic hardships, the culture here prioritizes family and interpersonal relationships over material wealth, a value system that resonates deeply with me. The kindness, generosity, and zest for life exhibited by the Mexican people starkly oppose the skepticism I felt in the US.

In these challenging times, being part of such a supportive and enriching community is a true blessing.

Sitting in a restaurant in Thailand, eating lunch, I see a group of 4 young people come in and sit down. They immediately take out their phones and begin scrolling. The waitress comes over, takes their order, and when she leaves, they go back to their phones. The food comes, they eat with one hand and scroll with the other. At the end of the meal, they pay the bill, stand up, phones in hand and walk out. Other than giving their order, not a word was spoken.

A Few weeks ago, one of our daughters and her husband, both in their late 30s, went to supper at a restaurant with us. As soon as we sat down, they took out their phones and began scrolling. After supper, I asked my wife, "Why did they want to go to supper with us?"

I'd rather spend my time alone or with my wife rather than with others who have cell phones.

This is so on point!! You captured the Zeitgeist of our times. Thoreau would be impressed “The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation”