There are moments in life when the borders between the physical and the metaphysical begin to blur—when the rhythmic clatter of a train becomes a kind of mantra, a meditation on movement and memory. That’s where I found myself, somewhere between Marrakech and Fez, the Moroccan countryside rolling past like an old newsreel, sun-washed and flickering with ghosts. I was seated in a train compartment with four strangers and Sherrie, each on their own pilgrimage, each quietly stewing in the strange, shared broth of transit.

One of them—a radiant woman from South Africa—had been to more countries than most people can name without a map. She spoke with the seasoned calm of someone who has long since given up trying to control the journey. That’s what travel does if you let it. It burns your ego down to the wick and leaves you open, raw, and ready for whatever comes next. That woman didn’t just know where she was going—she knew how to be wherever she landed. I admired that. I envied it.

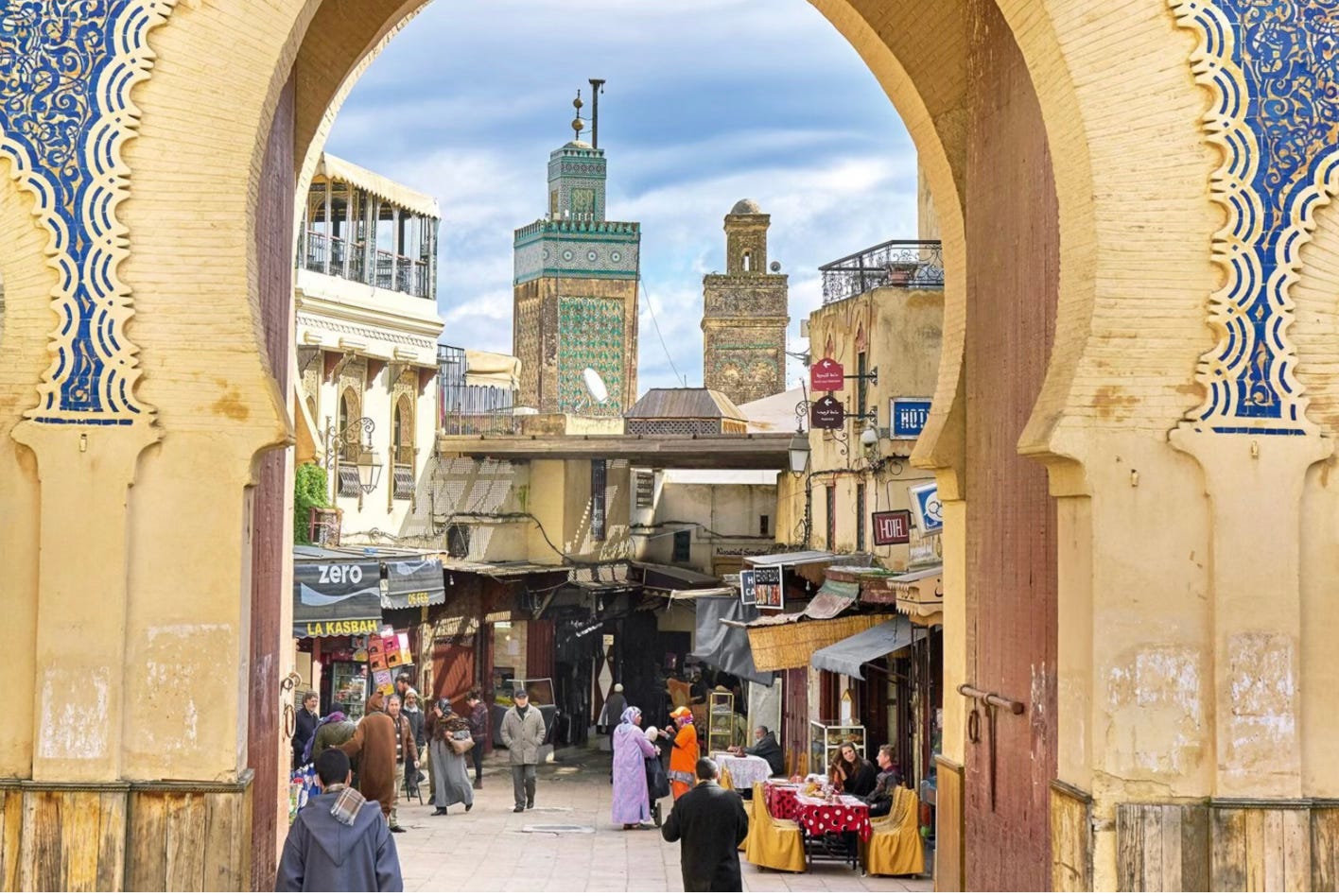

We’d just spent a week in Marrakech, sleeping in a riad owned by friends from Tucson—a little slice of the Southwest transplanted into the heart of North Africa. The juxtaposition was bizarre and oddly comforting. The building, like the city, felt alive: the creak of the stairs, the echo of voices in the courtyard, the smell of mint and stone and time. Marrakech is a fever dream, a swirling soup of alleyways and spice markets and mopeds that materialize out of nowhere like angry genies. There are no street signs. No logic. Just endless pathways leading to other pathways. It’s a Choose Your Own Adventure novel written by a calligrapher on hashish.

At first, I tried to navigate it with my usual Western logic. “If I went left, then right, then passed the donkey… I should be back at the café.” Nope. Try again. Every turn leads to another puzzle, another glimpse of something strange and holy. Marrakech doesn’t want to be understood. It wants to be felt. You surrender to it, or it eats you alive.

And we did surrender. We wandered. We got lost. We got found. We bought sweets we didn’t recognize and watched artisans hammer patterns into brass under the unforgiving sun. It was beautiful. It was baffling. It was exactly what we needed.

This is our first real immersion in Arab culture, and it’s been like discovering a new frequency on the radio—one that was always there, but drowned out by static. For seventy-plus years, I’ve lived wrapped in the barbed wire of American capitalism. I was born into it, schooled in it, judged by it. It’s a system that defines your value by your output, your possessions, your net worth. In America, the first question is always, “What do you do?” But that’s just code. What they’re really asking is, “How much are you worth to me?”

Five years ago, we made the move from the U.S. to Mexico, and that’s when the spell started to break. That’s when I first began to see how distorted American life had become—how we’d mistaken anxiety for ambition, and consumerism for identity. In Mexico, people still look you in the eye. They still care about your story, not your salary. No one asks what car you drive. They ask if you’re hungry. They ask how your family is.

It’s not that Mexico is some utopia. Far from it. Poverty is real and painful. Infrastructure can be unreliable. Bureaucracy can make you want to punch yourself in the kidneys. But there’s soul there. There’s humanity. People talk to each other in line at the pharmacy. Strangers become friends over tacos. In America, everyone’s scanning the room to see who’s a threat, who’s an ally, who’s the enemy. In Mexico, people laugh easily and mourn deeply and dance without needing a reason.

Now, in Morocco, I’m seeing shades of that same spirit. I don’t speak Arabic, but I don’t need to. The language of kindness is universal. Shopkeepers smile, even when you don’t buy anything. Old men nod with a twinkle in their eye. There’s a gentleness here—tempered by heat and history, yes—but still intact.

Interestingly, we’ve started telling people that we live in Mexico. Not because we’re hiding our nationality, but because it feels closer to the truth. When we said we were from the U.S., we got polite smiles… but also something else. A flicker. A twitch. The faint tightening of the jaw. You start to notice these things after a while. You get a sixth sense for how your passport lands in someone’s psyche. “Mexico,” on the other hand, seems to open doors. Maybe it’s the shared experience of being a former colony. Maybe it’s the global sense that America has become an unpredictable, swaggering drunk at the party. Either way, we’re leaning into our adopted home.

And then, of course, there’s Islam.

In the West, the word alone triggers alarms. It’s been hammered into our heads by decades of propaganda that Islam = terror. Islam = oppression. Islam = the Other. But here? It’s something else entirely. It’s a rhythm. A breath. A structure that weaves itself into daily life without suffocating it. The call to prayer at 4:30 a.m. startled me the first morning—somewhere between an echo and a song. It didn’t feel oppressive. It felt ancient. Like the city itself was waking up, whispering to the sky.

In Morocco, most people are Muslim, and their faith is not performative—it’s embedded. You see it in their patience, their hospitality, their deference to time. The country moves at its own pace. Friday is the holy day, and mosques swell with worshippers. But the streets don’t feel grim or somber. They feel grounded.

I’m not a religious man, but I recognize devotion when I see it. And I respect it when it’s rooted in humility rather than control. In Morocco, Islam doesn’t feel like a weapon. It feels like a compass.

Of course, this is a country where tourism is a lifeline. Being kind to strangers is not just a virtue—it’s a business strategy. But it doesn’t feel fake. It doesn’t feel forced. There’s an ease to it, a genuine pride in showing people their land, their food, their traditions.

And let me pause here to talk about the food

Moroccan cuisine is not food—it’s alchemy. It’s the scent of memory and the heat of longing served on a ceramic plate. Tagines bubble like cauldrons of comfort. Couscous arrives like a small mountain of perfection. Mint tea is poured with a flourish, a ritual, a cascade of liquid hospitality. Every bite feels like a secret handed down through generations. I didn’t just eat. I communed.

And that, maybe more than anything, is what I’ve taken from this journey: the sense that life doesn’t have to be a hustle. That the point isn’t to win or accumulate or dominate—but to connect. To listen. To share space.

America, in its current form, has forgotten that. It’s become a battleground of algorithms and outrage, where strangers are sized up like threats and compassion is considered weakness. We used to be a people who believed in the common good. Now we’re a nation of silos, screaming at each other across digital trenches.

Here, in Morocco, I feel something else. I feel community. I feel continuity. I feel… possible.

I don’t know what that means for the long run. I don’t know if I’ll end up living here someday. But I do know that this place—this train, this journey, this moment—is reminding me of what it means to be alive. Not productive. Not successful. Alive.

The train rumbles on. The South African woman is asleep now, her head leaning gently against the window. Outside, the landscape is shifting—palm trees giving way to rocky hills, ochre towns clinging to the earth like stories waiting to be told.

I sip the last of my tea. It’s lukewarm, but perfect.

Fez is still a few hours away.

But I think I’ve already arrived.

Until we meet again, let your conscience be your guide.

As-salamu alaykum! (Bienvenido...)

What a beautiful piece, Bret! Thank you :)