Enveloped by the gentle glow of a television and the charm of Saturday matinees at the Central Theater in the heart of West Hartford, as a teenager, I was spellbound by the allure of cinema. The medium of film intrigued me, offering myriad paths to weave compelling narratives.

The antiquated 8mm camera that once belonged to my father served as my personal portal into a universe with infinite creative possibilities. By the time adolescence took hold, I harbored an eager ambition to transform quaint family recordings into grand cinematic ventures.

When I was fifteen, the aptly named Art Cinema in Hartford, Connecticut, which also featured experimental theatre, became my sanctuary. My initial foray into foreign films were British comedies, the likes of Peter Sellers and Alec Guinness.

By the mid-1960s, London and Britain became more open-minded and fun-loving, which made their comedies bolder and more playful than their American counterparts. Movies made fun of British life, politics, and the social ladder, and they liked to show the everyday life of regular people in a funny but thoughtful way. This resonated ideally with my adolescent inclinations.

I soon found myself intrigued by a surge of European films from France, Italy, and Sweden. I discovered Truffaut and Godard, and the French New Wave, the cinematic movement characterized by a radical departure from traditional filmmaking conventions. Fellini’s films were a revelation, for their imaginative blend of fantasy and reality, often weaving dreamlike sequences with a vivid portrayal of the human experience. The highly controversial “I am Curious Yellow” from Sweden blended fiction with documentary-style filmmaking including candid discussions and scenes concerning sexual, political, and social topics, which led to its reputation as a highly provocative piece for the era.

By high school, I was entrenched in the study of film.

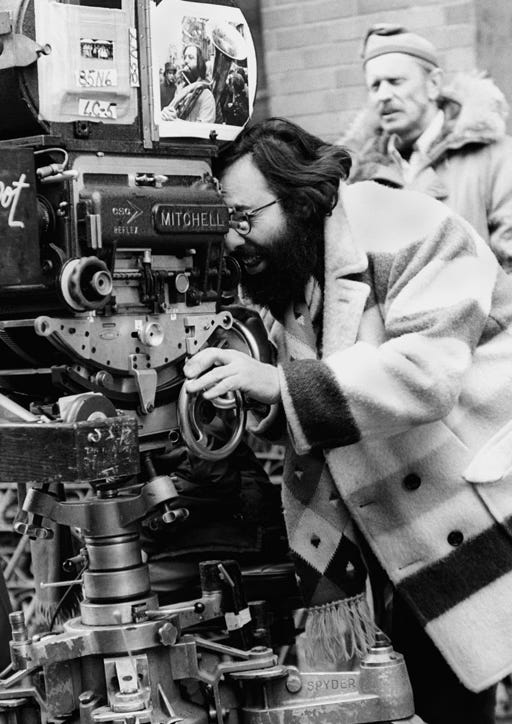

A pivotal encounter at seventeen sealed my fate: a University of Hartford screening of a new film, "Is Paris Burning?" with screenwriter Francis Ford Coppola there to discuss. He was dynamic. Very personable, intelligent, interesting. His words ignited a spark—I would study in film in college and become a screenwriter and director.

At the age of twenty-seven, Coppola had already penned two produced Hollywood screenplays: "Is Paris Burning?" and "This Property is Condemned." He had directed a low budget horror film produced by Roger Corman and was in the midst of directing his first studio movie, "You're a Big Boy Now." Moreover, he had just taken on the project of directing the musical "Finian's Rainbow." Hearing him discuss the craft of writing and directing films made it actually seem doable.

I consumed every film book and magazine available, and charted my course to NYU Film School. As often as I could, I went to New York for the day. Those New York excursions significantly broadened my film-viewing horizons. In those times, if you wanted to watch movies, and you lived in a smaller city, you had to set out on a trip. There was no cable TV with dedicated movie channels, no VCRs, and the idea of YouTube was far from conception.

My cinematic debut, an 8mm portrayal of a high school senior's life, marked my senior year. Rejection from NYU due to subpar grades led me to Hofstra University's theatre program, a choice serendipitously connected to Coppola, an alumnus.

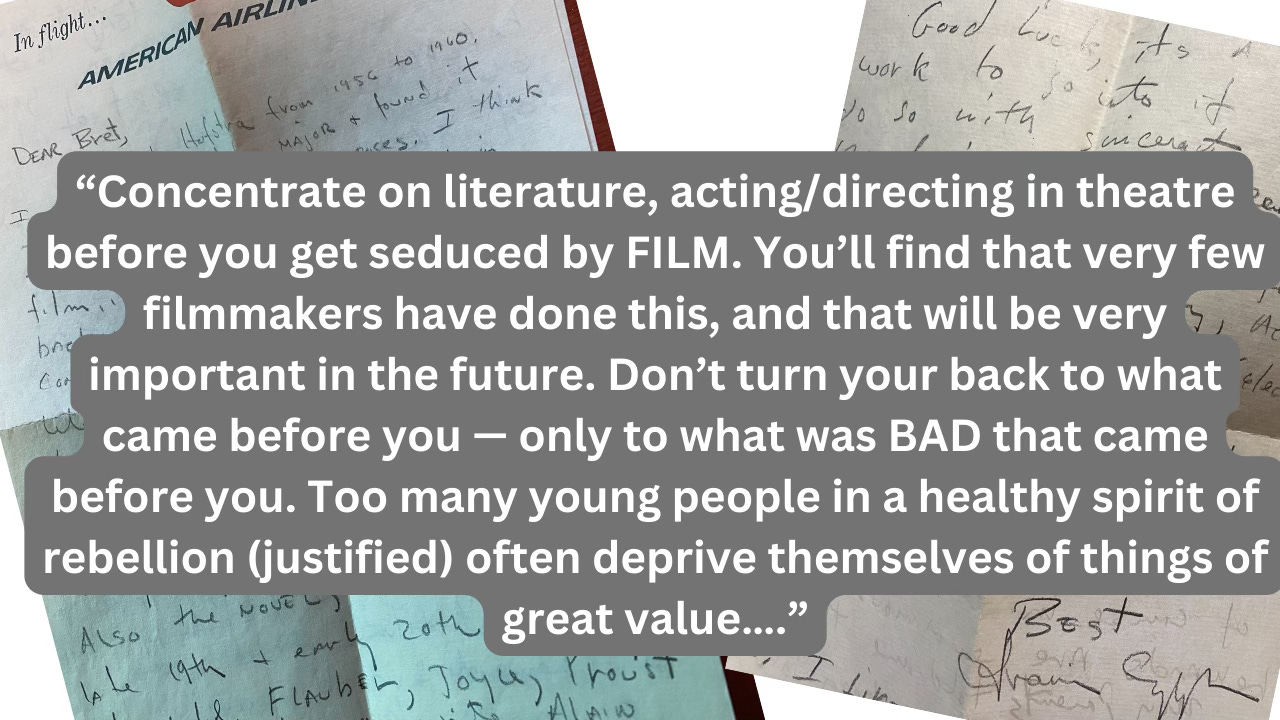

I wrote to Coppola at Warner Bros in Hollywood for advice, and he quickly responded.

Upon reaching Hofstra University in Hempstead, Long Island in September 1967, I discovered that Coppola was filming "The Rain People" nearby. Through some stroke of luck, I managed to arrange a breakfast with him at the Garden City Hotel. He was incredibly friendly, exactly the kind of mentor one could only hope for. After our meal, he introduced me to his assistant, George Lucas, and they showed me around the bus they had converted into an equipment van, equipped with everything needed to shoot a Hollywood feature with just a bare-bones crew.

The chance to be an apprentice on Coppola's "The Rain People" was almost in my grasp, yet a mix of self-doubt and parental pressure kept me from seizing it. Such an experience might have altered the entire course of my life, but at eighteen, I struggled with self-assurance, and my parents were firm about not letting me leave school, not even for a semester, to work on a film. They were supportive of my aspirations but were equally worried about the practicalities of earning a living in filmmaking.

My academic pursuits at Hofstra soon took a back seat to taking the LIRR into New York to go to jazz clubs and stellar double features at the Thalia and New Yorker theaters on the Upper West Side. I also discovered my first middle eastern restaurant, Cleopatra, on 95th Street and Broadway.

A steadfast year culminated in triumph when I gained admission to NYU Film School. From the time of my television appearance at six years old on the Howdy Doody Show, I'd harbored a deep-seated desire to relocate to New York. That dream was finally becoming my reality. Immersing myself in the dynamic and captivating swirl of late 60s New York was like stepping into a world of wonder. It marked a formative period of personal evolution and discovery for me. Juggling the responsibilities of driving a taxi with the demands of film school, I steered through the exciting landscape of my early independence, usually sleep deprived.

At that stage, I found myself navigating life independently due to my parents grappling with their own personal and professional challenges. I financed my $2,500 annual NYU tuition through student loans, and sustained myself with part-time work. After my sophomore year, I began driving a taxi in the summer. Balancing night shifts behind the wheel with daytime classes wasn't simple, and this demanding routine made it challenging to seize all the opportunities that NYU Film School had to offer.

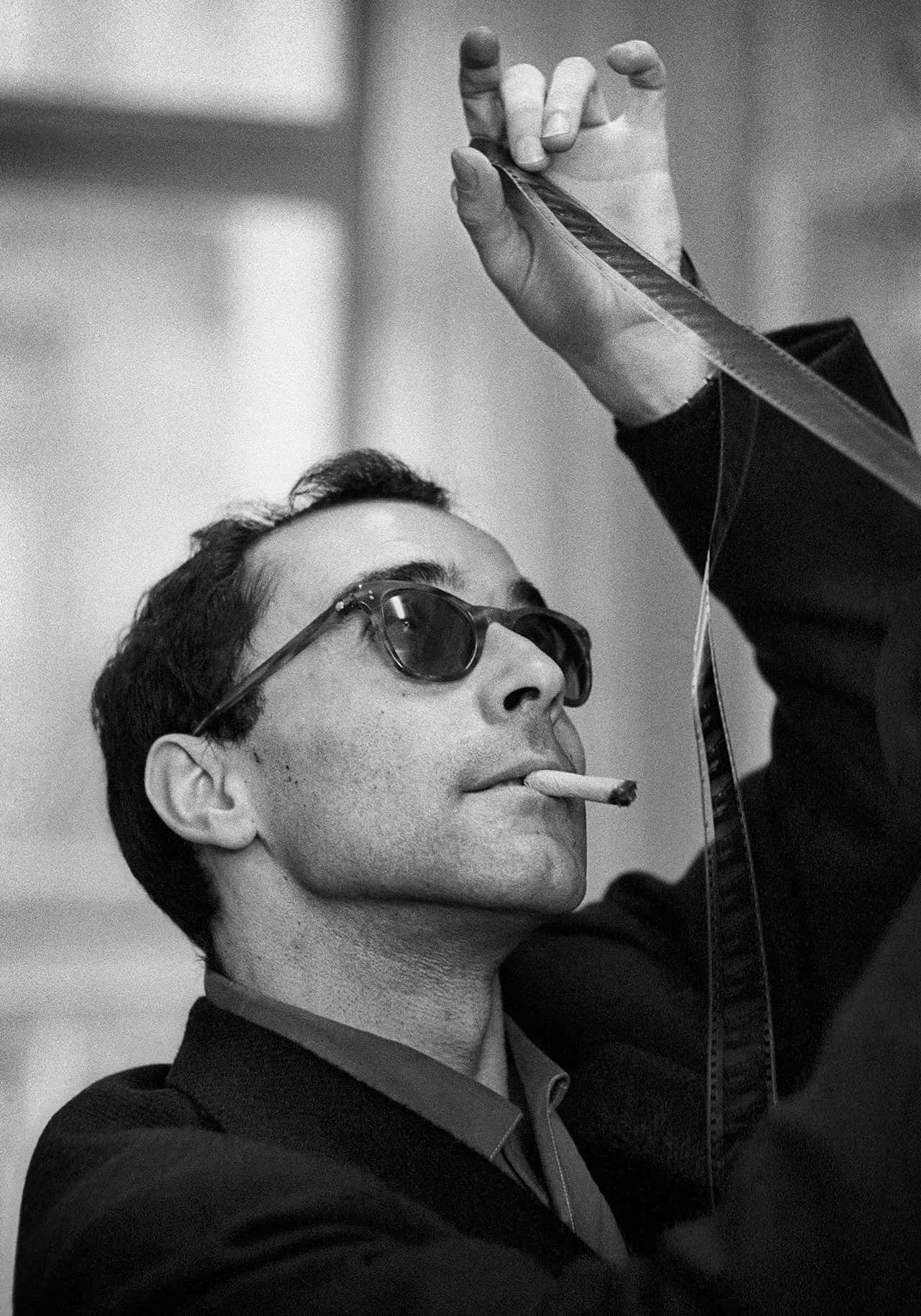

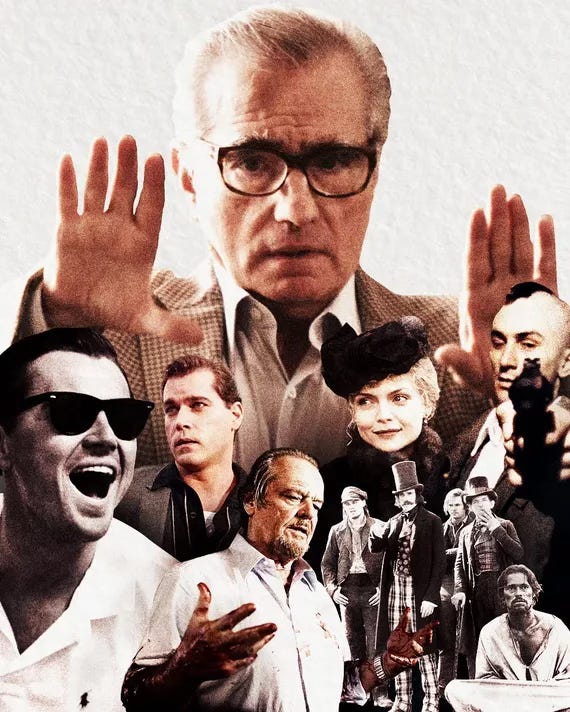

By the time I got there, Martin Scorsese, an NYU alumnus, had taken up a full-time professorship. Referred to affectionately as Marty, he was the school’s most beloved instructor. I enrolled in number of his classes, ranging from film appreciation to production. Marty's fervent love for film, coupled with his extensive knowledge, was already becoming the stuff of legend. His enthusiasm for the art of cinema was infectious, a trait that remains to this day. The film industry was in the midst of a significant shift, with voices like Coppola's at the forefront, and movies like "Easy Rider" were emblematic of the new wave that was opening doors for the next generation of filmmakers. Scorsese became a founding member of what is called The Film School Generation, along with Brian DePalma and Steven Speilberg.

I produced several shorts at NYU and my Senior project, for Marty’s production class was “Rough Ride,” about one night in the life of New York City taxi driver. He praised the film and several years later, produced his own take on the subject, “Taxi Driver,” which starred his collaborator, Robert DeNiro.

While he was teaching at NYU, Marty was multitasking as an editor for the "Woodstock" documentary as well as working on his own project, “Who’s That Knocking At My Door.” At that point, his future impact on the world of cinema and the significant role he would come to play were not yet evident. But he was a very involved, enthusiastic presence at NYU. Helpful, caring, and always anxious to discuss any aspect of filmmaking.

The last interaction I had with him occurred on the debut day of “Mean Streets,” right in front of the Sutton Theatre on East 57th Street, where the film premiered. He was pacing, observing the crowd with a mix of nervousness and expectation. “Mean Streets” turned out to be his initial landmark film, and what followed is now well-documented in the annals of film history. Marty has become one of the most important filmmakers of the modern era.

During my time at NYU Film School, I immersed myself in the various facets of filmmaking: cinematography, sound design, editing, lighting, screenwriting, and directing. I found a deep connection with writing, which led me to concentrate my efforts in screenwriting After penning several screenplays that didn't quite meet my expectations, I found tremendous inspiration in Ben Hecht, an accomplished screenwriter responsible for seventy films and the author of an autobiography I hold in particularly high regard, "Child of the Century." My fascination with Hecht's work persisted beyond my NYU days, leading me to write a play centered on his efforts in Jewish activism. This interest further evolved into a more recent documentary feature exploring Anti-Semitism in America, dedicating a portion to Hecht's life and contributions.

Post-graduation from NYU, I secured a position with a modest-sized firm in New York, where I was involved in the production of documentaries and industrial films. However, the routine of filming and upkeep tasks related to the job soon grew monotonous. I decided to leave the position (in hindsight, a hasty decision) to produce a ten-minute short film that delved into a recording session with a saxophonist renowned for his collaboration with Alice Coltrane, Memphis born Frank Lowe. The film was “Street Music,” released in 1973. Interesting that my first film out of NYU was a documentary about Jazz. Then a thirty year gap in filmmaking before I became the Jazz Video Guy in 2004. During that time, I wrote hundreds of articles, liner notes and booklets, and also seven plays that were produced by a theatre company I co-founded.

The following summer, I rented a tiny house on Fire Island with some friends. On a Sunday evening, while taking the train back to the city, I was searching for a seat and happened to spot Mel Brooks, who owned a summer residence on Fire Island, sitting by himself. I approached and asked if I could take the seat beside him. He agreed, letting me know that the seat was open, but he wasn't available for a conversation. He had work to do. And lots of it.

During my teenage years, Mel Brooks was a constant source of laughter for me. His performances as the 2000 Year Old Man, along with his appearances on 1960s talk shows with Steve Allen and Johnny Carson, were particularly memorable. Rooted in the Borscht Belt tradition, Brooks took a daring and unconventional turn in his comedic approach, beginning with his work alongside Sid Caesar. Mel truly embodied the spirit of a comedic wild man.

In the loony, no-brakes rollercoaster of Mel Brooks' comedy, "fear" is just another four-letter word for "yawn." The Brooklyn native dances on the razor's edge of comedy, jabbing at the untouchable, the sacred cows grazing in the field of "thou shalt nots" with a grin wide enough to swallow the sun.

For me, he stands shoulder to shoulder with Lenny Bruce and George Carlin—those high priests of the profane, the sacred jesters who flicked at the nose of propriety with a devil-may-care attitude. They didn’t just push the envelope; they set it on fire. And while the flames rose, so did the profound truths in the smoke signals of their punchlines.

Even though he said he had work to do, I had to ask him a question: “Mr. Brooks, I’m a filmmaker and I really enjoyed “The Producers” and “The Twelve Chairs.” Are you working on a new movie?” That opened the floodgates.

Mel and I spoke for nearly ninety minutes and shared a cab back downtown to the Village. As we sped through Long Island en route to New York, Mel animatedly brought to life the script of his newly written film, "Blazing Saddles.” It was more than a reading, it was a performance that had me in fits of laughter. The other passengers looked on in astonishment, perhaps wondering if we had just fled from an institution. Having him perform a live version of one of the greatest comedies in film history was an unforgettable experience. We also spoke at length, about a number of historic films including a favorite of his, the silent German horror classic, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. In addition to comedy, Mel Brooks knew quite a bit about filmmaking.

Fifty years have flown by since then. Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola are now in their eighties, still active in the industry. Remarkably, at ninety-three, Mel Brooks recently earned a writing credit on the Hulu Series "History of the World Part 2." As for me, my journey didn't lead to becoming a screenwriter or director of feature films. Instead, I found my calling as the Jazz Video Guy, a role I embrace with deep gratitude. Today, I'm still working, learning, and enjoying a vibrant life in Guanajuato, Mexico. Maybe I’ll make it into my 90s, maybe just until next Wednesday. That’s why every day is so important.