A work of fiction based on a true story, as told to me by Walter Bishop, Jr.

March, 1972.

Gideon Bass was famous, in a way, because he played with Bird. The New York native served as Bird’s pianist intermittently just before the co-creator of Bebop caught a cab, in 1955. Everyone in Charlie Parker’s musical orbit was a somebody in Jazz.

Regrettably, Gideon's life mirrored Bird's own ill-fated descent into substance abuse. Parker's early demise echoed a Shakespearean tragedy, characterized by a spiral of self-destruction that his followers, including his last man at the keys, tragically emulated.

For years after the death of Charlie Parker, Bass held onto the hope of gaining the recognition he deserved for his talent in playing and composing. However, each time he felt he was making headway, a setback would occur, making it increasingly difficult to maintain his optimism.

Battling addiction and overwhelmed by misfortune, Gideon gradually disappeared from the limelight. A fervent admirer of Bud Powell's piano style, which is centered around horn-like melodies, Gideon possessed talent and a unique musical voice. But for decades, he faced endless challenges and was constantly scrambling for gigs. The prospect of securing a record deal was an unattainable dream for him.

Despite this, Gideon remained a vital member of the Jazz community, cherished by both friends and peers. Sixty years ago, the Jazz world was considerably more intimate. Centered in New York, the Jazz Mecca, it was like one big, wild, and wonderfully chaotic family.

But in the overall scheme of the jazz business, an oxymoron at best, he was a nobody, and that bugged the shit out of him nearly every day of his life.

Then he met Sophia Lancaster, a reformed beatnik who truly loved the music and the musicians who played it. She had a been a regular on the scene at clubs for years. Gideon knew her face, although they had never spoken until one night at Count Basie’s club in Harlem. An attractive Jewish brunette, she wasn’t the type of gal who sought redemption by hanging with African Americans. She was, as the expression goes, just good people.

Gideon was always something of a ladies man; he’d had a string of attractive girl friends. He dressed well, could talk the talk, and had genuine respect for women because of the love and strong influences of the two West Indian women in his life, his mother and grandmother.

Sophia and Gideon clicked almost immediately and within a few months, they were living together. Sophia became his biggest booster and as a team, she helped him get a few more gigs. But the mid-60s was a tough time for Jazz in New York. As television became ubiquitous, clubs were closing and they were fewer performance venues. And unlike the swing era, when big bands ruled, rock became the musical lifeline for teenagers.

Several musicians concluded that relocating to Los Angeles would enhance their personal and professional experiences, leading to a significant migration. Among those who relocated were Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, and Freddie Hubbard. Following their lead, Gideon also opted to move. Sophia agreed with the decision, and together, they exchanged their New York apartment for a modest Studio City crib.

In Los Angeles, the music scene was primarily centered around studio work, with musicians recording for movies, television, commercials, and collaborating in sessions. Consequently, live gigs were few and far between. Like most major cities, LA had its share of clubs showcasing notable artists. Gideon, however, found himself piecing together occasional gigs at venues best described as shitholes. These were the kinds of establishments where musicians were offered tepid beer and the stage was adorned with ashtrays, seldom emptied, containing remnants of cigarettes from performers who had played there months earlier.

While Sophia worked as a secretary, Gideon became despondent. He hated the fact that without Sophia’s income, they simply couldn’t survive on the West Coast. By the time he got to LA, he was in a methadone program so he wasn’t strung out, but not working took its toll.

Even though a cloud of doubt hung over him, he kept writing, and developed a musical theory that he detailed in a book. His Theory of Fourths became very popular with many musicians. But aside from attracting a few new students, his situation didn’t change.

After working a gig in the Valley one night, where only three people showed up, he decided he’d had enough. He felt he had no choice but to end his life. He just couldn’t take it anymore. Gideon saw no future in LA, and the thought of scuffling for years and years in New York made him sick. But he didn’t want to die in LA, where Sophia would find him. So, the next morning, without waking Sophia, he went to the bank and withdrew most of his savings, and caught the next flight to JFK.

After landing, Gideon’s plan was to check into the Americana Hotel, on 7th Avenue and 52rd Street, and then go up to Harlem where he could easily score the necessary barbiturates. Before returning to his hotel, he planned on visiting a barber to have his head shaved, and then to a block in Harlem where junkies would go to cop, and in dark alleyways, shoot up. He intended to distribute twenty-dollar bills, motivated by his past experiences. Fifteen years earlier, he had been in the same position as those he aimed to help, often hoping for someone to come by and offer him some financial assistance, so he could get high.

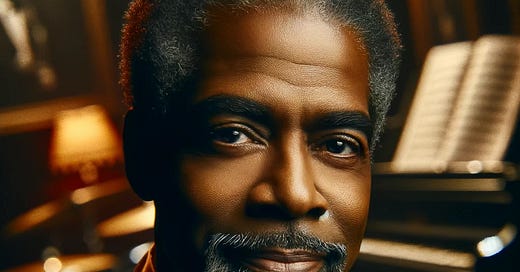

Acquiring the necessary sleeping pills was a quick task, taking only about five minutes. Familiar with the location, he faced no issues in this part of his plan. Then, he visited his longtime barber, who was still in business, to shave off his beard and get a clean head shave. He had a habit of shaving his head at pivotal moments, marking the end of one chapter and the start of another. This time, he believed, he was embarking on what he perceived to be the final chapter of his story.

When he got to 114th Street, just off of 7th Avenue, he took out his roll of twenty dollar bills and walked the block, handing out a crisp new bill to anyone who looked like they needed it. The junkies went wild. He went unrecognized as serious Jazz musician but Gideon felt great, feeling he was really helping people who really needed this kind of lift.

Then there was a change to his plan. His friend, pianist Bobby Timmons, was working downtown at the Vanguard with a Trio. Gideon figured that if he was going to leave this world, instead of a final meal, he wanted to listen to one final set of great music, played by a friend.

Even though he still had a pocket full of cash, he rode the A Train downtown to 14th Street, and walked over to the Vanguard. As soon as he opened the door and walked down the steps into the club, he felt the energy and anticipation of the packed house. He got a seat a few tables from the tiny stage and when Bobby Timmons walked to the stage, he passed Gideon, but didn’t recognize him. Each time Bobby looked at the audience, he would see Gideon, and for a moment seemed to realize who it was. Gideon avoided eye contact and looked away. Bobby did this a few times, but forty minutes into the set, Gideon left the club. They never spoke.

Back at his hotel room, he took twenty sleeping pills, stripped down to his underwear, and got into bed. Within fifteen minutes, he was asleep, figuring he wouldn’t wake up.

But when he did, he was in a hospital room, surrounded by his family, his father and mother, his grandmother, his two sisters, and Sophia, who had flown in from the coast.

A cleaning woman had knocked on the door of his hotel room to clean it, the morning after what was supposed to be his last night on earth. She found him in the bed, tried to wake him, and came upon the empty bottle of sleeping pills. She called an ambulance and Gideon ended up at Bellevue, where his stomach was pumped.

Looking into the faces of a group of people who loved him, unconditionally, Gideon began to cry. At first he couldn’t speak, as he was still pretty spaced out from the barbiturates. What got to him was the love he felt in his hospital room. They weren’t there to criticize him, just to offer their support. In the magnanimity of that moment, he broke down, sobbing, deeply sorrowful for what he had done.

Once everyone saw that he was going to be okay, one by one, they kissed and hugged him, and then left the room. Except for Sophia. She held his hand and finally spoke.

“Why didn’t you tell me, Gid, I could have helped you.”

He was silent, looking for a way to answer her.

Finally, “I was ashamed baby, I turned into such a burden. You’ve been working so hard. I couldn’t make any money.”

“I don’t care about money. I care about you and your music. That’s what matters.”

Even though Gideon was aware of it, his preoccupation with survival and making a mark in the music industry had caused him to inadvertently neglect the love of Sophia and his family. His brush with death served as a catalyst, allowing him to view his life from a new perspective.

He came to understand that the only aspect of his life he truly had control over was creating his music. Once the notes drifted away from the keyboard, their fate was no longer in his hands. His gratitude for his family and Sophia, coupled with the sheer joy of music, eclipsed all else. Suddenly, everything else seemed insignificant.

Upon his return to Los Angeles, Gideon was transformed. The profound love he experienced had not only healed him but also fortified him. The lingering doubts of his past and the uncertain trajectory of his career lost their weight in his mind. Wealth and fame, once coveted, no longer mattered. His aspirations had dissolved, leaving behind a singular desire to immerse himself in the music he cherished. This sense of rebirth, often a gift from the brink of death, now defined him.

The story reminds me of myself. Ahem. Read the novel, most of which is true. http://bit.ly/1QynBVD

There's a free version at Smashwords.com.

I never knew about this earlier part of his life. But he kept the hairstyle!