Jazz and the Mafia

Mobbed up Birdland owner Morris Levy threatened musicians with a baseball bat.

It's 1992, and through the grapevine of my late pal Bob Belden, I land the gig of a lifetime – penning the booklet for Maynard Ferguson’s Roulette recordings for Mosaic Records. For a jazz aficionado like me, who cut my teeth on Maynard's electrifying early 60s big band sound, it was like striking gold.

So, I shoot a message to Maynard Ferguson himself, buzzing with excitement. But what do I get? Radio silence. Nada. Then, another buddy clues me in, whispering a name that sends chills down my spine: Morris Levy.

Levy's not your run-of-the-mill music mogul. He was a heavy hitter in the jazz club scene, a big cheese in music publishing, and a titan in the independent record industry. The guy was the brains behind Roulette Records and a key player in the birth of the legendary Birdland jazz club.

But here's the kicker: Levy's as notorious as they come, a character straight out of a noir film. We're talking about a guy with a reputation for violence and shady Mafia connections that run as deep as the grooves in a vinyl record.

It dawns on me: Maynard's Roulette recordings weren't just the product of his musical genius. They were intertwined with Levy's dark, twisted world. The saxophone's wail in those tracks might as well be the sound of the underworld, a melody played to the tune of the Mob's shadowy dance.

In the frenetic world of early 20th century jazz, the shady underbelly of the Mafia wove itself indelibly into the music's evolution. Picture this: Louis Armstrong, a 16-year-old cornet prodigy, lands his first paying gig in 1917 in a New Orleans dive bar. But this isn't your average joint; it's a Mafia front, a bustling hub of gambling and vice, operated by the local Sicilian mob.

Fast forward to Chicago, 1924. Armstrong finds himself in the heart of the Jazz Age, playing at Joe Glaser’s Sunset Club. Who's behind the scenes? None other than Al Capone himself, a jazz aficionado and club co-owner. These mobster-run venues, often the epicenters of illegal activities, became sanctuaries for jazz, a genre initially snubbed as “colored music.”

In the gritty streets of New Orleans, Chicago, and Kansas City, local mobsters, often from marginalized ethnic backgrounds themselves, felt a strange kinship with African American musicians. They controlled the jazz clubs, creating a complex, often exploitative dynamic. Think of it as a modern-day plantation system, with crime bosses like Capone and Lucky Luciano at the helm and black musicians as their entertainers.

But it wasn't all bleak. These lawless club owners protected their black artists from the era's rampant racial violence. Their illicit profits funded lavish jazz orchestras, allowing musicians to thrive artistically without the pressure of commercial success.

However, the Mob's shadow loomed large. Clubs like the Cotton Club and Plantation Club, with names evoking the slaveholding South, were stark reminders of the racial inequalities still rampant, even in supposedly progressive areas like Harlem. Here, Duke Ellington spun his jazz magic to segregated crowds.

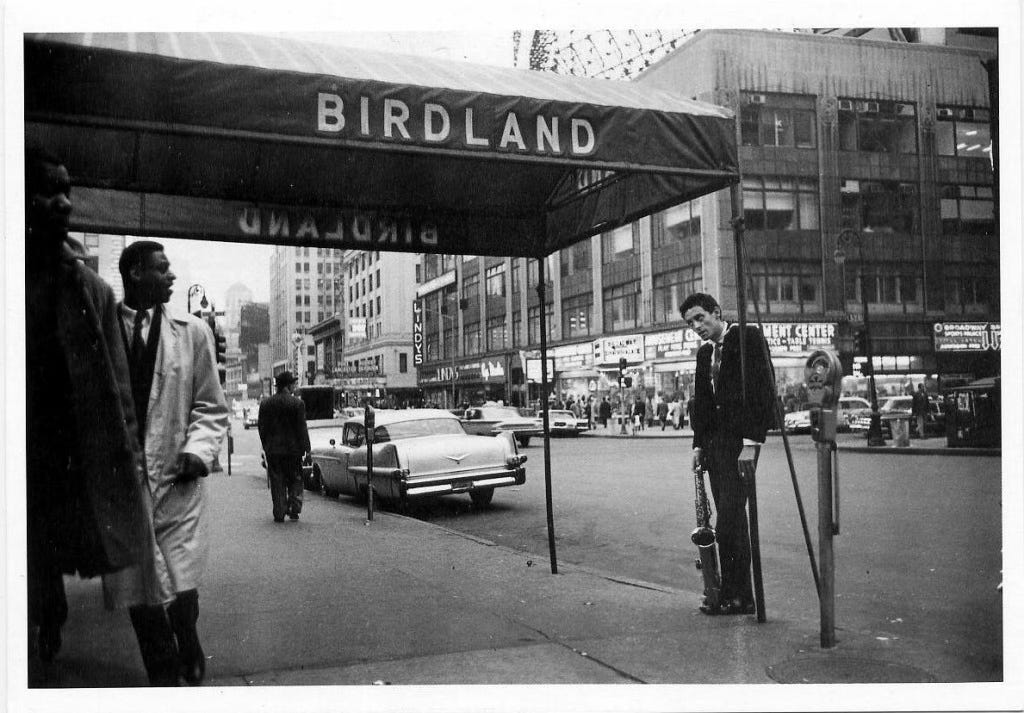

Birdland in New York, named after jazz legend Charlie “Bird” Parker, epitomized the Mob's deep ties to jazz. Morris Levy, its owner, was no mafioso, but he rubbed shoulders with them, fascinated by their murky world. The club was a mobster haven, with the Genovese crime family often in attendance.

Then came the night of January 26, 1959. Birdland was buzzing, packed to the brim. Irving Levy, the club's manager and Morris's brother, confronts an uninvited guest, leading to a tragic altercation. Levy is stabbed, dying as the Urbie Green Big Band plays on.

Morris Levy, though a respected civic figure, was notorious for his exploitative practices in the music industry. His record label, Roulette Records, often strong-armed artists, and he was known to threaten those who resisted his terms with a baseball bat.

Despite his eventual conviction for these shady dealings, Levy eluded jail, his life cut short by colon cancer in 1990. His story, like many in this era, is a tumultuous mix of jazz brilliance and the dark, gripping influence of the Mafia.

When Levy died, he left a legacy of shady dealing in a career that spanned more than 40 years. Maynard Ferguson, who regularly played Birdland with his Dream Band, was also signed to Roulette Records. Here, Dennis DiBlasio, who played baritone sax with Maynard, remembers a discussion with Maynard about his Roulette recordings. And Michael Franzese, who spent years working with the Mob, shares his take on Morris Levy. Finally, we hear from the man himself, just after he was indicted.

Yes, a great but scary book.

This is fascinating stuff -- thanks! I remember the Strawberries part on the Boston news and was sort of amazed it was the same legendary guy. Aside from the great _Hit Men_, another book on this , one that is probably not on many jazz fans' radar, is Tommy James' _Me, the Mob, and the Music: One Helluva Ride_. It's a fun and fast read, the writing is not bad, and the stories are outrageous. It tells some of this from a personal perspective, the career of one artist who was caught inside it from an early age. It's interesting that James has some mixed feelings at the end, although the relationship was sometimes really scary and cost him a huge amount of money in royalties on his many hit records.