Within days of arriving in New York, John Lennon and Yoko Ono quickly immersed themselves in the avant-garde art scene. Among their new circle of friends, they were part of a large gathering—over 250 guests—celebrating the birthday of entertainment attorney Allen Klein’s wife, Betty, at their Riverdale home. Klein’s professional relationships with Lennon, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky all ended poorly. In Yiddish, the language of my ancestors, Klein was both a “gonif” (thief) and a “shyster” (dishonest attorney).

The party was filmed by Jonas Mekas and Shirley Clarke while Andy Warhol snapped countless polaroids. Jonas and Shirley both released their films many years later. Jonas, a major figure in the avant garde film movement, a Village Voice film columnist and one of the founders of the Anthology Film Archives, eventually edited his footage of the party (in his usual style) under the title of "June 12, 1971 at Klein’s".

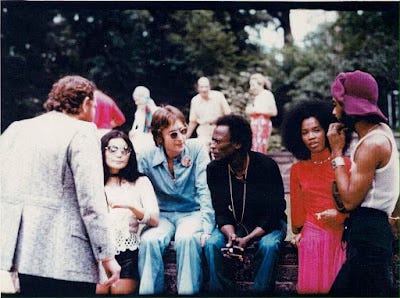

Though John Lennon often claimed he wasn’t a fan of jazz, he did meet Miles Davis at Klein’s house. There’s video footage of them playing a casual game of one-on-one basketball, with John’s psychedelic Rolls-Royce parked in the background. The party drew a wide array of guests, including Andy Warhol, but it was Miles Davis who John was photographed with the most that day.

Although they came from different musical worlds, the Beatles had a broad interest in jazz, among other genres, and were known to explore diverse musical influences.

Paul McCartney, in particular, has spoken about being influenced by John Coltrane’s music. The Beatles’ experimentation with unusual chord progressions, extended harmonies, and more complex song structures on albums like Revolver and Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band reflects not only popular music influences but also avant-garde jazz and classical elements that artists like Coltrane were exploring in the mid-60s. George Harrison’s interest in Indian music, partly inspired by the jazz world’s fascination with non-Western scales and improvisation—something Coltrane also delved into—further connects their musical worlds.

I’ve been watching Beatles documentaries on the Film Retrospect YouTube channel, along with Peter Jackson’s multipart reworking of The Beatles: Get Back, which captures the recording sessions for the Let It Be album in January 1969. These documentaries delve deeply into specific sessions, showing how the band transformed a few initial ideas into fully realized recordings.

Jackson’s film highlights the band’s creative process during rehearsals and recording, culminating in their iconic rooftop concert—their final live performance together. It’s fascinating to watch them shape a song, witnessing firsthand how their music came to life.

For those of us who lived through the music of the late ’60s, this content feels like being a fly on the wall, creating songs that became part of our consciousness. It is fascinating to see how they worked together in the most intimate way. By that time, they had been brothers for nearly a decade. The four lads from Liverpool experienced a remarkable spiritual and musical evolution in the ’60s, and these films offer a unique glimpse into how they changed the world.

By 1971, the Beatles had stopped recording together, with each member pursuing their own musical path. John Lennon was fully immersed in his solo career, with the release of Imagine marking a pivotal moment in his artistic and political journey.

Imagine stands as one of Lennon’s most iconic albums, blending personal, political, and philosophical themes. The title track, “Imagine,” became an enduring anthem for peace and unity, reflecting his vision for a better world.

Lennon’s activism was increasingly woven into his music. Tracks like “Gimme Some Truth” expressed his frustration with political corruption, while the single “Power to the People,” released earlier in 1971, was a direct call for social and political action.

As Lennon became more vocal about anti-war and human rights issues, his music echoed his passion for peace and revolution. His outspoken stance on the Vietnam War put him on President Nixon’s enemies list, and although Lennon had a deep love for New York, he faced ongoing immigration battles that added stress to his life.

In 1971, Lennon was at a creative peak, merging introspective songwriting with daring political statements. The release of Imagine solidified his solo career and became a defining moment in his evolution as both an artist and activist.

1971 was a transformative year for Miles Davis as he continued to revolutionize jazz by blending genres and pushing the boundaries of improvisation with a new wave of musicians.

In the midst of his electric period, Miles was exploring uncharted territory in jazz fusion, drawing heavily from rock, funk, and psychedelic influences. Having already released groundbreaking albums like Bitches Brew (1970), which redefined the jazz fusion landscape, he was working on more material that would later emerge as Live-Evil (1971) and On the Corner (1972). His live shows were marked by sprawling, freeform improvisations and intricate rhythms, with a band of young, innovative players like Keith Jarrett (keyboards), Jack DeJohnette (drums), Gary Bartz (saxophone), and Michael Henderson (bass). During this era, his music became more abstract and rhythmically intense, as he increasingly relied on electric instruments to build dense, layered soundscapes.

By this point, Miles had moved far from the modal jazz and bebop styles that made him a household name in the 1950s and ’60s. His new fusion of jazz, rock, funk, and avant-garde influences created a darker, funkier, and more rhythmically charged sound.

Yet, 1971 also saw Miles facing personal struggles, including health issues related to drug use, which affected his productivity and touring schedule. Still, his creative output remained influential, even as his public persona became more rebellious. Embracing the counterculture, Miles often appeared in flamboyant, rock-inspired clothing and maintained a bold, outspoken presence both on and off stage.

In 1971, I was twenty-one, just starting my career as a filmmaker after studying at NYU Film School. Jazz was the pulse of my life. When I arrived in New York in the late ’60s, the music scene was exploding. Miles was at the forefront of jazz fusion, the Loft Scene was vibrant, and bebop legends were mentoring the next generation of musicians.

There was a palpable sense of hope and excitement in the air, a feeling that we were all part of something significant—a movement that would leave its mark on culture and change the way we thought about art. Change wasn’t something to be feared; it was embraced.

Looking back at the music, films, drama, and art of that period—the creative foundation of my life—I feel incredibly lucky and inspired. That music and those films are part of me. I’ll always be listening to Miles and the Beatles.

A few years ago, I produced a podcast series called Miles ‘71, which is available on YouTube. This episode highlights Miles Davis’s performance at the 1970 Isle of Wight Festival, which drew the largest audience in jazz history. Saxophonist Gary Bartz, who was part of the band that day, shares his memories of the flight to the festival and the unique reception they received from the rock-oriented crowd. The group included Miles, Gary, Chick Corea and Keith Jarrett, keyboards: Dave Holland, bass; Jack DeJohnette, drums and Airto on percussion.

Wow! Didn’t know about the meeting between Lennon and Miles. The photos and short home movie are epic! Exciting time indeed!

Miles was "Miles Ahead" in hearing and bringing us forward. with him and his bands. Grateful for this rare trip. He indeed didn't need words, as they weren't his language.