The Narrative Surrounding Blue Note Records Is As Captivating as the Music it Produced.

Jews and Jazz, Part 1

Blue Note Records, unparalleled in its impact as a small-scale record label, emerged from the vision of German Jewish immigrants in America. Founded in 1939 by Alfred Lion, the son of a Jewish architect from Berlin, the label's inception was intertwined with Lion's tumultuous journey fleeing persecution in his homeland. Lion's encounters with violence against minorities both in Germany and the United States underscored the pervasive challenges faced by immigrants.

Lion's passion for jazz was ignited during his teenage years in 1925 when he witnessed a captivating performance by African American jazz pianist Sam Wooding in Berlin. Despite immigrating to the United States in 1926, Lion faced adversity, including an assault by a fellow laborer who harbored animosity towards immigrants. Forced to return to Germany to recuperate, Lion's subsequent attempts to escape Nazi Germany eventually led him back to Manhattan in 1938. It was there, inspired by landmark jazz concerts like "From Spirituals to Swing" at Carnegie Hall, that Lion found renewed purpose.

The founding trio of Blue Note, which included Max Margulis, a Marxist vocal coach, and critic Emanuel Eisenberg, shared Lion's commitment to social justice and appreciation for jazz. Despite maintaining their day jobs, they launched Blue Note in 1939, a pivotal moment coinciding with heightened Jewish awareness of African American struggles, exemplified by Billie Holiday's performance of "Strange Fruit" at Café Society.

Blue Note's ethos was shaped by a deep empathy for marginalized communities and a profound reverence for jazz and its practitioners. In an industry often characterized by exploitation, Lion and his colleagues stood out as passionate advocates, infusing their venture with quasi-nonprofit principles. Reflecting this ethos, Margulis penned a manifesto, signed by Lion and Eisenberg, outlining their commitment to elevating the artistry of jazz while championing social causes:

“Blue Note Records are designed to serve the uncompromising expressions of hot jazz or swing. Direct and honest hot jazz is a way of feeling, a musical and social manifestation, and Blue Note records are concerned with identifying its impulse, not its sensational and commercial adornments.”

Although no more commercially oriented than his landsmen, Eisenberg’s own trajectory was complex. He authored short fiction in the Yiddish-accented mode popularized by humorist Leo Rosten, including one tale that appeared in 1938 in the New Yorker.

The discovery of common threads in racism, whether aimed at African Americans or Jews, mirrored the philosophical vibes of Lion and his crew when they kicked off Blue Note, sparking a sense of solidarity. No coincidence, the label's debut hit came from none other than George Gershwin's stash – "Summertime," by Sidney Bechet, blending Jewish and African American musical mojo.

Lion, always the maverick, demanded that the standard 78 rpm record size be stretched to a lavish 12 inches, a move typically reserved for the highbrow classical cats rather than the pop scene's 10-inch norm. To him, jazz cats were nothing short of modern-day classicists, a view that history has overwhelmingly endorsed.

When World War II erupted, Margulis and Eisenberg bounced to different gigs, leaving a vacancy filled by Lion's childhood buddy, Francis (aka Jacob Franz) Wolff. Wolff wasn't just any old mate – he was a shutterbug extraordinaire, who hung out with Milt Gabler, another jazz-loving Jew with a knack for labels, based at the Commodore Music Shop on West 42nd Street. Gabler was a Blue Note supporter early on, hooking them up with distribution and sales spots.

Wolff, caught somewhere between the dramatic flair of his Jewish contemporary Philippe Halsman and the raw energy of Erich Salomon, a pioneering German photojournalist renowned for his candid and unobtrusive style of photography, Wolff napped memorable photographs at Blue Note sessions. These masterpieces, once locked away in Lion's secret stash, now shine in galleries and all over the web. Wolff was not focused on posing his subjects; his unobtrusive presence enabled him to capture musicians in the act of creation.

Despite their names, Lion and Wolff weren't exactly lion-hearted or fox-like with performers; in fact, artists remembered them with a warm glow. Lion and Wolff showed their loyalty by being the first to put the spotlight on the keyboard maestro Thelonious Monk back in '47, when no other label would touch him, sticking with him for five tough years even when his records tanked, putting Blue Note's future at risk.

Blue Note reeled in some heavy hitters. John Coltrane, Art Blakey, Miles Davis, Dexter Gordon, Herbie Hancock, Bud Powell, Sonny Rollins, Horace Silver, for starters, and they all laid down some of their most timeless tracks for the label, immortalized in Wolff's action shots.

Blue Note did hit some bumps along the road, morphing from a little indie into something much bigger by the late '60s. But in 2012, it felt right when they named a bridge after Lion in Berlin, connecting his childhood stomping grounds with the rest of the city. Alfred Lion and Francis Wolff weren't just about making music; they were about building bridges, linking Jewish music lovers with the creative spirits of African American artists, leaving behind recordings that still mesmerize and memories that'll never fade.

Accordingly, Blue Note Records holds immense significance in the history of jazz.

Blue Note was known for its pioneering recording techniques. They used high-quality equipment and innovative studio setups with the help engineer extraordinaire Rudy Van Gelder, which allowed musicians to showcase their talents with exceptional clarity and fidelity. This helped capture the nuances of jazz performances, contributing to the development of the genre.

Unlike many other record labels at the time, Blue Note prioritized artistic freedom for its musicians. Lion and Wolff believed in giving artists the creative autonomy to express themselves fully. This approach attracted some of the most talented and innovative musicians of the era, leading to the production of groundbreaking and influential recordings.

Blue Note Records was known not only for its exceptional music but also for its iconic album cover designs. Reid Miles, the label's graphic designer, created visually striking and influential cover art that became synonymous with the Blue Note brand. These designs not only helped distinguish Blue Note releases on record store shelves but also contributed to the label's overall aesthetic appeal.

The label also played a significant role in shaping the cultural landscape of the mid-20th century. Its recordings captured the spirit of the times and reflected the social and political movements of the era. The label's music became synonymous with the vibrant and diverse cultural scene of cities like New York, where many of its artists were based.

Blue Note Records was important to jazz because it provided a platform for artistic innovation, fostered creative freedom, and helped define the sound and image of modern jazz. Its contributions to the genre continue to be celebrated and studied by musicians, historians, and enthusiasts alike, worldwide.

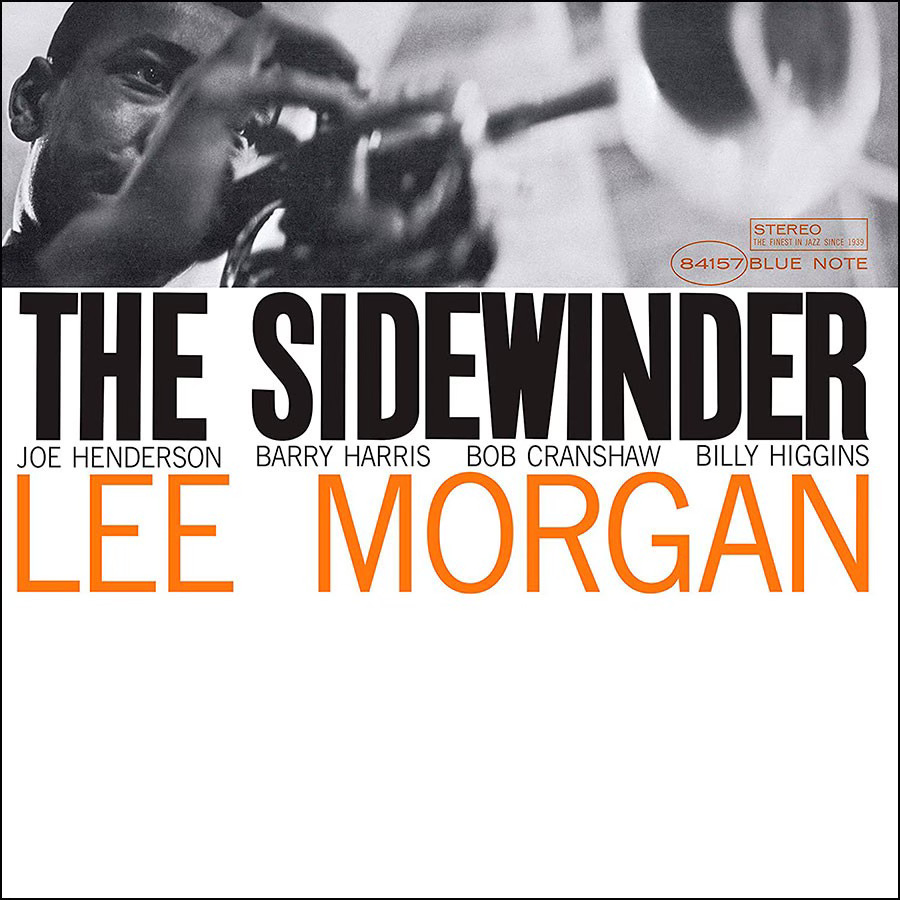

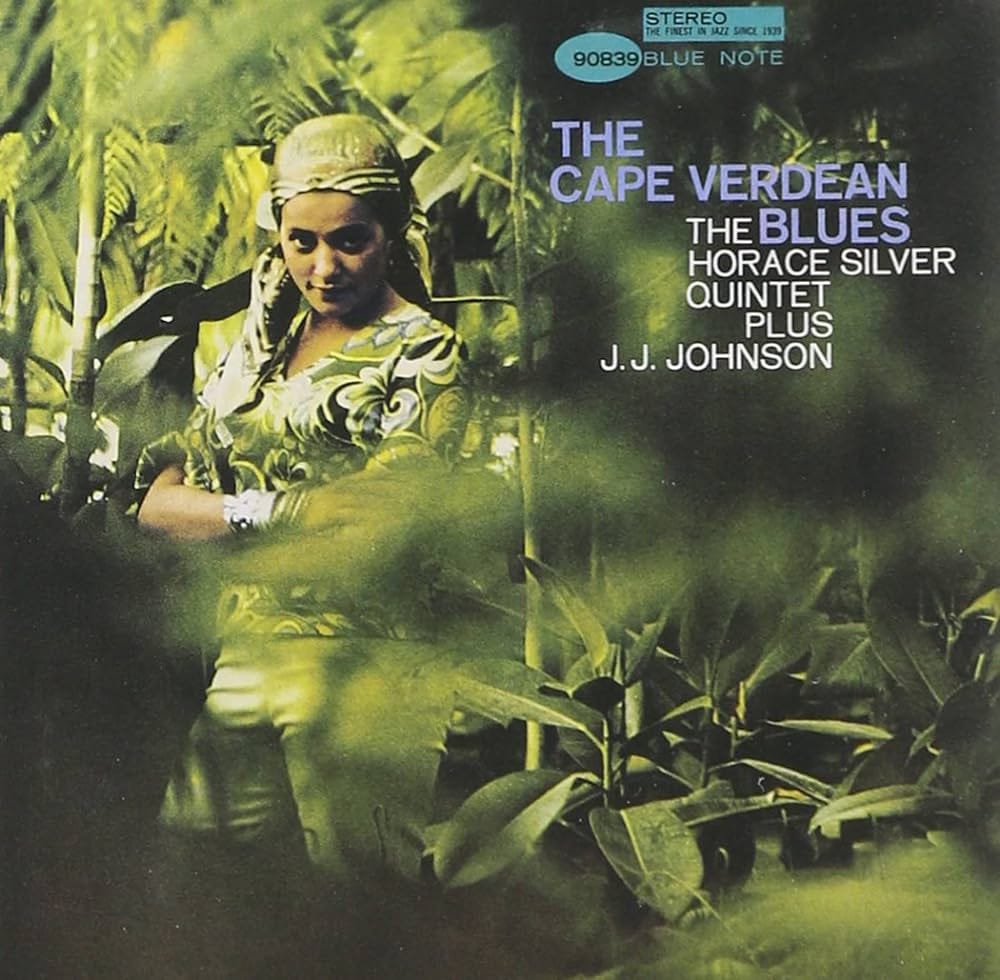

I still groove to the first two jazz LPs I snagged at thirteen: Lee Morgan's "The Sidewinder" and Horace Silver's "Cape Verdean Blues." That music hits just as hard as it did sixty years back. Early on as a jazz listener, I was drawn to music that had a groove.

When Liberty Records acquired the label in 1967, Lion and Wolff's original vision took a backseat to a more commercially driven strategy. The label's commitment to its artists waned, leading to a decline in its allure. However, in the mid-80s, Bruce Lundval and Michael Cuscuna breathed new life into Blue Note. Cuscuna spearheaded a dynamic reissue program, unearthing hidden gems from Blue Note's archives and revitalizing its catalog with newfound classics.

An important component of the Blue Note story — the album covers. Here’s a superb mini-doc from Vox about Blue Note’s amazing covers.

I'm currently developing a documentary focused on Horace Silver. His experiences with Blue Note Records offer a unique insight into the broader narrative of the label.

Alfred and Francis gave Horace total artistic freedom. The recordings he did in the 50s and 60s for Blue Note established him as a founding father of hard bop, and were among Blue Note’s most popular releases.

The situation at Blue Note changed in 1965 when the label was acquired by Liberty Records. Following this acquisition, Alfred Lion found it challenging to work within the larger corporate structure and retired in 1967. Around the same time, Reid Miles, known for his iconic album cover designs, ended his association with Blue Note. In the subsequent years, most albums were produced by Francis Wolff or pianist Duke Pearson. Pearson had taken over A&R responsibilities from Ike Quebec, who passed away in 1963. However, both Wolff and Pearson departed from the label in 1971—Wolff passed away, and Pearson left for other opportunities.

Horace Silver had eight recordings remaining on his contract and, driven by a growing interest in spiritualism and mysticism, he began to infuse his compositions with lyrics that addressed spiritual, healthful, and socially conscious themes. His highly successful ensemble, the Horace Silver Quintet, was rebranded as Horace Silver and the United States of Mind.

Record company executives were resistant to changing the musical direction that had previously brought them success. They questioned why Horace would want to alter a winning formula. Nevertheless, Horace was eager to explore new creative avenues. His initial release with the United States of Mind did not impress his new Blue Note bosses. They chose not to market or distribute the music as vigorously as they had with Horace's earlier works. After the third and final United States of Mind recording, the label didn’t renew Horace's contract,

If Bruce Lundval and Michael Cuscuna hadn't revived Blue Note in the 80s, the label might have become inactive. Today, under the umbrella of Universal Music Group, Blue Note thrives with a vigorous reissue program and new recordings from a wide range of artists producing diverse, captivating music.

More about It’s Got To Be Funky - The Life and Music of Horace Silver.

U've got perspective!

Keep writing & revealing yr Vid stash.

Valuable history and context. Mostly new to me.

The Jew/Jazz connection is a rich stream. Great that you're prospecting.

Looking forward to more gold.