Great bands carry the seeds of their own implosion like a ticking time bomb, waiting to blow. It’s inevitable. The hotshot sideman comes in wide-eyed and hungry, soaking up wisdom, fame, and some much-needed swagger from the leader. But then the itch starts. Confidence swells. He’s got fans now. The whispers in his head get louder: “Why not go solo?” And just like that, the cracks start to show. Great art often comes at the breaking point, right before the whole thing burns down.

Cue Kind of Blue. Miles Davis’ iconic sextet was a powder keg of genius, and the fuse was lit. Bill Evans was the first to jump ship, but not before Davis dragged him back for one last job—laying down those impressionistic keys that shaped the album. By the time the record hit the shelves, Wynton Kelly was warming the piano bench. Then Cannonball Adderley flew the coop, teaming up with his brother Nat to chase their own glory.

And Coltrane? Oh, Trane was biding his time, scribbling his own manifesto. Prestige, Roulette, Blue Note—he was already a name. But signing with Atlantic in ’59? That was the rebirth. Barely a heartbeat after the final Kind of Blue session, Coltrane was in the studio unleashing Giant Steps. By the end of the year, Coltrane Jazz would drop, with Davis’ rhythm section backing him up. The man was ready to take the wheel. Miles knew it too, but he wasn’t about to lose his golden saxophone just yet. So he sweet-talked Trane into one last hurrah—a European tour in spring 1960.

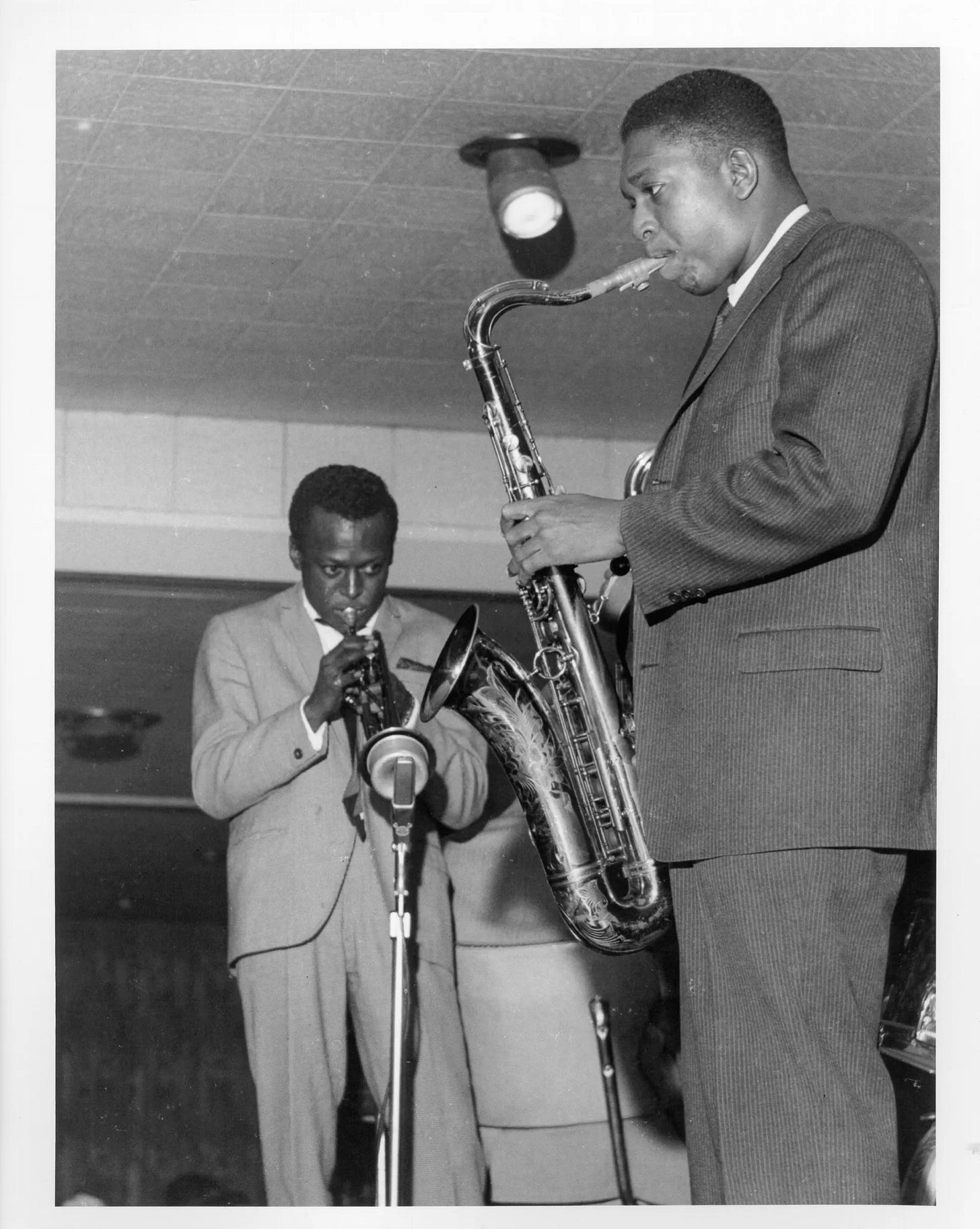

The Paris gig at the Olympia Theatre on March 21 was the opener for Norman Granz’s Jazz at the Philharmonic circus. Davis shared the stage with Stan Getz and the Oscar Peterson Trio, and the whole thing was caught on tape by Europe 1 radio. The setlist was classic Miles, with hits from his catalog and So What from “Kind of Blue.” Miles, ever the cool commander, played like a man on a mission: sharp, poised, brimming with soul. He twisted standards with extended turnarounds, signaling solo shifts with sly melodic cues, a precursor to the coded transitions he’d use later in the continuous sets of his electric years. Wynton Kelly was a revelation too, all swing and taste, his interplay with Miles a masterclass in understated brilliance. Behind them, Paul Chambers and Jimmy Cobb anchored it all, the ultimate rhythm machine.

But Coltrane? Oh, Coltrane stole the show, even if he didn’t want to be there. Word is, Trane spent the tour in a storm cloud of his own making—practicing like a man possessed, barely speaking to anyone. He supposedly carried just a small bag with one suit. That tension bled into his playing, and what came out was nothing short of a sonic assault. This wasn’t the “sheets of sound” Trane of yore. No, this was something else entirely. He toyed with melodic fragments, warped them, blew them apart. He overblew, shrieked, and dug into the sax like it was fighting him. Split tones, multiphonics, unhinged upper-register screams—it was raw, primal, unrelenting.

The audience didn’t know what hit them. Some cheered; others booed. Jazz itself seemed to be fracturing in real time, factions forming between the traditionalists and the avant-garde. Davis, ever the enigmatic ringleader, let Trane run wild. Maybe he sensed a revolution brewing, even as the crowd erupted in chaos. Later, Miles would quip about Coltrane’s inability to end a solo: “Why don’t you try taking the horn out of your mouth?” But on that night, he gave Trane the runway.

The result? A document of modern jazz teetering on the edge of the abyss. More than six decades later, it’s still a visceral ride. Miles, Trane, the whole band—this wasn’t just a gig. It was a moment, a raw snapshot of art in transition, fueled by genius, conflict, and the inevitability of change.

The Paris concert was the last time John Coltrane performed live with Miles Davis. By this time, Coltrane was increasingly focused on his own music and had already formed a strong vision for his quartet, which would soon become one of the most influential groups in jazz history.

This European tour in 1960 marked the end of Coltrane’s tenure with Davis’s quintet/sextet. Although Coltrane had been pivotal in the success of Kind of Blue and earlier Davis albums, their musical directions were diverging. Coltrane was exploring modal and avant-garde jazz, while Davis’s sound was evolving in other ways. Following this tour, Coltrane officially left Davis’s group to focus on his own band, leading to the creation of landmark albums such as Giant Steps and My Favorite Things.

The recordings from the 1960 European tour, including the Paris concert, are a historical treasure, showcasing the transitional phase of both artists.

March 21, 1960 Olympia Theatre, Paris, France

MILES DAVIS QUINTET

Miles Davis- trumpet, John Coltrane- tenor saxophone, Wynton Kelly- piano, Paul Chambers- bass, Jimmy Cobb- drums

1st set

All of You (C. Porter)

So What (M. Davis)

On Green Dolphin Street (N. Washington-B. Kaper)

2nd set

Walkin' (R. Carpenter)

Bye Bye Blackbird (R. Henderson-M. Dixon)

'Round Midnight (B. Hanighen-C. Williams-T. Monk)

Oleo (S. Rollins)

The Theme (M. Davis)

Concert recording, broadcast by Europe-1

When I was a kid, back in the 70's, vs now in 2025, Columbia Records had this promotion that you'd find in the newspaper. Buy 12 records for one penny, and then buy 4 (or 6) albums at full price in one year. Well, I managed to find a penny, tape it to the return form, stick it in an envelope (free postage) and send it to Columbia and I got a stack of records. Man, I thought I hit the lottery. One of the records I picked was Miles Davis Greatest hits, which I think is most songs from recordings with this quintet and some with Ron, Herbie and Tony. I think the version of "Walkin'" is from this concert. I was exploring because the few jazz records I had, Count Basie with Harry Sweets Edison and Eddie LockJaw Davis blew me away. I'm only 13 or so and there were no record stores in my little town in Long Island or jazz radio. And those colorful ads all caught my eye. For some kids it is baseball cards, but my eyes opened wide. I remember getting Chuck Mangione and Grover Washington which I could understand and then when I put Miles on, I didn't get it at all. Miles sliding all over the place on My Funny Valentine and Coltrane playing like scrambled eggs. But I'm glad I stuck with it and basically taught myself how to listen to and appreciate jazz while all the kids in school were listening to the Police and other pop/rock bands which never really caught my attention at the time. I wanted to hear trumpets and saxophones.

But boy was mom pissed when she saw the letters from Columbia that I needed to send them money for the other 6 albums and she wrote them a mean letter about obligating a kid into a contract. I think they released me. I'm pretty sure I played Columbia back later in life when I got a job and bought stacks and stacks of albums. Nobody told me in the 70's that one day all the music would be free on the internet. Nobody even told me there would be an internet. Figured that one out myself. This music lives forever in my heart!!!

This is such a great concert recording. Thank you for sharing.