In the early 70s, pianist Walter Bishop, Jr. and his first wife Valerie moved to Los Angeles from Manhattan. After playing with Charlie Parker for five years before his death in 1955, Bish was still seeking new musical experiences and an escape from the hectic New York scene. The move represented a fresh chapter in his career and life.

Though his time with Charlie Parker earned recognition, Walter Bishop, Jr. was more of a favorite among fellow musicians than a household name. The jazz business, both then and now, was notoriously difficult to navigate. Despite his affable and warm-hearted nature, after leaving Parker in the late '50s, Bishop found himself in an industry tightly controlled by a small elite who held sway over record deals, distribution, and live performances. While he could always find work in small clubs and as a sideman, the overall jazz scene remained frustratingly complex and often limiting for even the most talented players.

There were two major migrations of jazz artists from New York. The first occurred a century ago when Black musicians began moving to Europe in search of less racism and more opportunity. In France, Sidney Bechet became national heroes. On the other side of the pond, jazz musicians were treated with dignity and respect, even though at that time, most were African-Americans. The exodus continued for decades as musicians like Ben Webster, Kenny Clarke, Bud Powell, Dexter Gordon, and Johnny Griffin found Europe far more welcoming than the U.S.

After World War II, New York musicians gradually began relocating to the West Coast. Los Angeles offered studio work, though live performance opportunities were somewhat limited. However, the more relaxed lifestyle attracted many, with the migration peaking in the late 50s to the early 70s. A number of Walter Bishop, Jr.'s friends, including Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Freddie Hubbard, and Joe Zawinul, had already made the move to LA.

Bird Lives

The jazz world was stunned by Bird’s passing in 1955, leaving many musicians wondering what was next. Bish was a jazz musician and nothing but, so he was eager to expand his musical knowledge. After fifteen years, he had a pretty good handle on bebop, a complex, demanding style. He learned nearly everything about the piano and its possibilities from Bud Powell. Bish was so inspired by Bud that he carried a photo of him in his wallet as a constant source of motivation.

In the early days of bebop, mastering the style was no easy feat, but Bish rose to the challenge, eventually spending five years alongside one of jazz’s greatest icons, Charlie Parker. His musical ear was unparalleled.

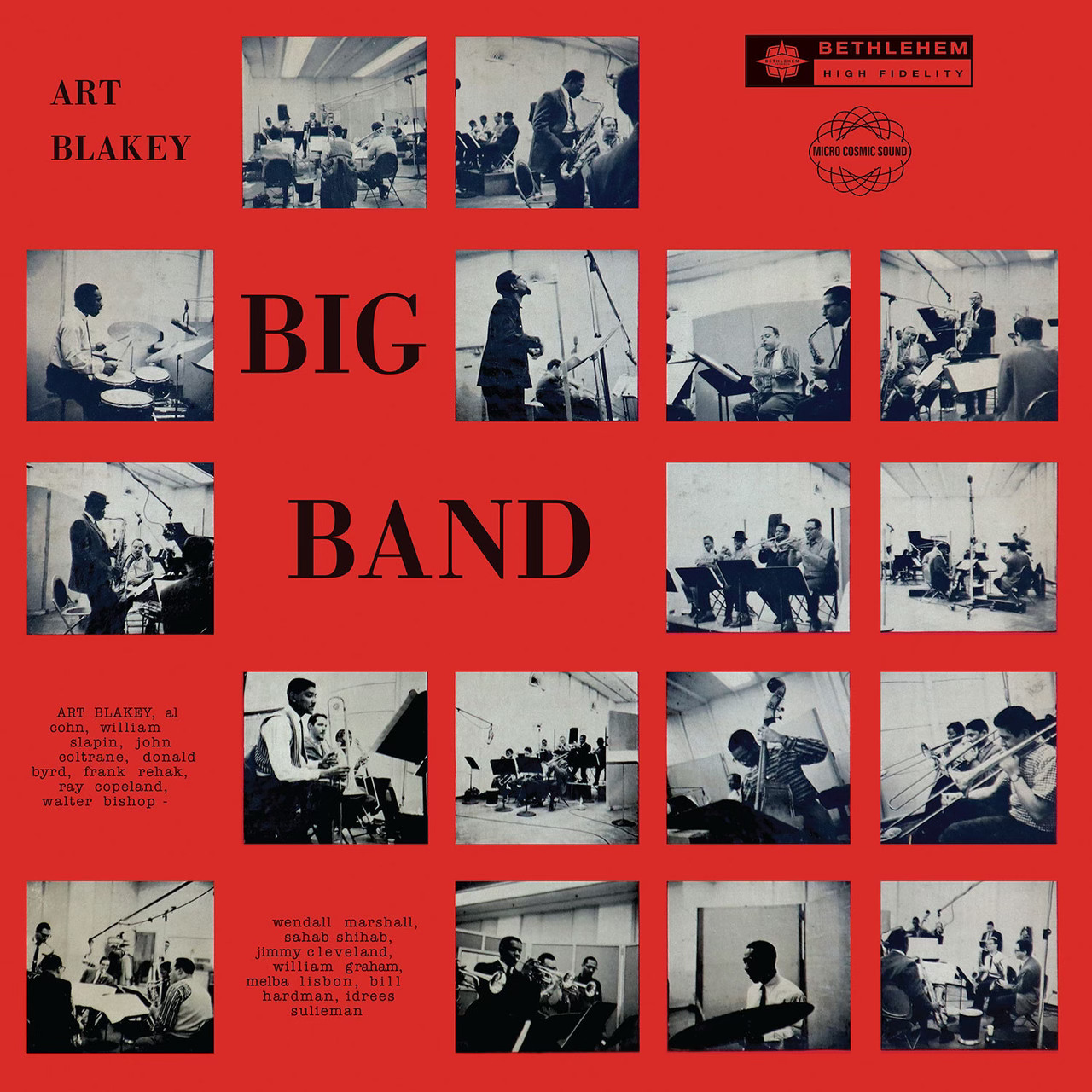

Bish also played with Art Blakey in different Jazz Messengers lineups, starting in the late 1940s. He was the pianist on Blakey’s 1957 big band recording with John Coltrane and Donald Byrd out front. This was a rare big band outing for Bish but a cloud hung over the session. He couldn’t read music.

Bish's keen listening skills and ability to apply what he heard to the music naturally, allowed him to excel in performances and recordings.

Then came the Blakey session. The quintet tracks, featuring Coltrane in a fresh context, were recorded while Trane was working with Monk at the Five Spot, and are valuable.

Recording the big band tracks presented challenges. The arrangements by Tadd Dameron were harmonically rich, lyrical, and sophisticated—difficult to fake, no matter how sharp one’s ear.

Bish managed to get through the session, but the experience pushed him to finally learn to read music. Having been serious about bebop and piano as a teenager, he realized it was time to delve deeper into the melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic possibilities of jazz.

After he arrived in LA, he began studying with Lyle 'Spud Murphy, known for his pioneering work in jazz orchestration and his development of the "Equal Interval System" (EIS), a method of music composition and arranging.

Bish built on what he learned from Spud Murphy, developed his own Theory of Fourths, which became the foundation of his improvisations and compositions. Although he had dabbled in writing earlier in his career, this new approach ushered in a more prolific phase for his music. In addition to playing, he was writing regularly.

Other LA musicians took notice of the Theory of Fourths, incorporating it into their own musical toolkits. Bish wrote a theory book and taught, to share his concept.

Eager to record and showcase his new music, Bish's first major project in this period was Coral Keys, released on Black Jazz Records in 1971. Bish composed all seven tracks, featuring two different groups. The first four tracks include his friend Harold Vick on tenor, soprano, and flute, Reggie Johnson on bass, and Idris Muhammad on drums. The last three tracks feature Alan Schwartzberg on drums and a young Woody Shaw on trumpet, in addition to Vick and Johnson.

Coral Keys was the second release for Gene Russell’s Black Jazz Records. Bish blended his bebop roots with elements of soul and funk. Freddie Hubbard later recorded one of the tunes, Soul Turnaround. Interestingly, in the late 1970s, Bish returned to New York and re-recorded two of the compositions, Coral Keys and Soul Turnaround, on electric piano, for his 1977 Soul Village album on Muse Records.

I met Bish in ‘76, when he was playing with Clark Terry. I knew him from his work with Bird and we immediately connected. Seeking greater recognition, he asked if I would interview him, which I did. I sent the interview to DownBeat and it was published the next year, my debut as a jazz journalist. I was present at the Soul Village session and eventually wrote those liner notes, the first of many such assignments. We also began working on his autobiography, a project that, unfortunately, never materialized.

For the next two and a half decades, Bish and I were very close, until he passed away from lung cancer in 1998 at the age of seventy. Bish was not only a superb musician but also a dear friend—the first true friend I made in the jazz world.

When Coral Keys was released in ’71, it flew under the radar for most people. Walter Bishop Jr. had hoped for more, and so did the folks at Black Jazz Records. But the breakthrough never came. The album was good—damn good—but it just didn’t sell.

Bish had the band locked in tight. They flowed effortlessly between modal jazz, hard bop, and post-bop, like it was second nature. Harold Vick’s soprano sax solo on the title track was something special—clean, melodic, with shades of Coltrane. The rhythm section, anchored by Idris Muhammad on drums and Reggie Johnson on bass, kept everything grounded. And then young Woody Shaw’s trumpet came in on the final tracks, elevating the whole session to another level.

Bish wasn’t trying to hide his influences. Bud was his main man, but he was open to everyone who had something to say, musically.

Sadly, Coral Keys slipped away.

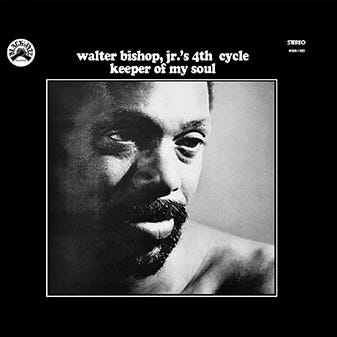

Bish’s second album for Black Jazz Records, Keeper of My Soul, was different. In ‘73, he went back to the studio with a new sound, a new band, and a new purpose. The album was credited to The 4th Cycle. The Cycle of 4ths, the rhythms and techniques Bishop had honed over years of playing, learning, teaching was not front and center.

This record had weight. It had spirit. Bishop had been chanting and practicing Japan buddhism and you could feel it in the music. It was electric, ambitious, and different from anything he did before. One composition was dedicated to his buddhist buddies, Those Who Chant. With Ronnie Laws on sax and flute, Gerald Brown on bass, and Woody Murray on vibraphone, they played free, wild, and loose. There were moments of Latin fire with Blue Bossa, and a version of Summertime so strange and funky, it pulled you in and wouldn’t let go.

Yet again, it fizzled out quietly, without the impact it deserved.

Today and forever, the music lives on YouTube.

Listen to Coral Keys, Bish’s 1971 Black Jazz Records release.

Listen to Keeper of My Soul, Bish’s 1973 Black Jazz Records release.

Bret, Sweet tribute to another one of the great jazz Cats tragically under appreciated

Yeah!!! For him to go from Bird to this. This was in the air at the time. I think it had to do with social, political ( broadly) changes being fought for and won. But man that fight is not over now.

Anyway this is is some great music and thank you for putting it up Brett.