In the late sixties, as a student at NYU Film School living in the East Village, my life was immersed in creativity, discovery, and music.

By day, I studied filmmaking under Martin Scorsese—Marty, as we called him—a man whose encyclopedic knowledge of cinema spanned from the earliest silent films to contemporary works, and whose infectious passion could captivate anyone willing to listen. Marty delved beyond the technical craft, unpacking the historical, cultural, and emotional impact of films with an intensity that made it clear he was destined for greatness. Even then, his relentless drive to push creative boundaries set him apart, and it came as no surprise when he emerged as a pivotal figure in the New Hollywood movement, redefining American cinema with groundbreaking films like Mean Streets and Taxi Driver, forever altering how stories were told on screen.

NYU Film School in the early ’70s was an especially thrilling place to immerse oneself in the art of filmmaking.

At night, I drove a cab, plunging into the electric chaos of late-’60s New York—a living classroom in urban life where cultural revolutions, political unrest, and youthful rebellion converged on every street. From the bohemian hum of Greenwich Village to the gritty pulse of Harlem, I witnessed the city’s stark contrasts and its kaleidoscope of characters: drifters, intellectuals, social climbers, radicals, artists, and power brokers, each revealing a fragment of the city’s evolving soul. Driving wasn’t just a job—it was a crash course in survival, grit, and human nature, offering me a front-row seat to a city and an era undergoing profound transformation.

Whenever I could, I dove into the dynamic music scene, with the Fillmore East a fifteen minute walk from my East Village apartment, shared with my film school buddy John Singer. Nearby, Slug’s Saloon, the legendary jazz club, added to the vibrant cultural fabric of my world. Across town, the world famous Village Vanguard, where I rubbed shoulders with the jazz legends who would later become my friends, in the kitchen.

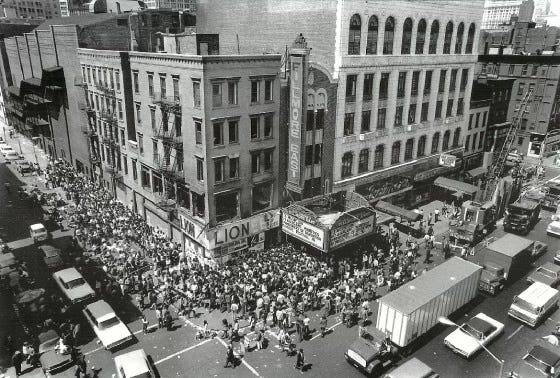

The Fillmore East, often dubbed “The Church of Rock and Roll,” was more than a venue; it was a cultural institution. Promoter Bill Graham’s vision was to elevate rock music to high art, offering a transformative experience that transcended entertainment. From March 8, 1968, to June 27, 1971, the Fillmore East became a cornerstone of the counterculture movement and a key part of the burgeoning rock scene. It wasn’t alone in this endeavor—Graham’s reach stretched across the United States with the opening of the Fillmore West in San Francisco, where the music explosion of the late ’60s was just as vibrant. Together, the Fillmore East and West helped define the era, solidifying Graham as one of the most influential concert promoters in history.

Located at 105 Second Avenue, next door to the NYU film school and the famed kosher dairy restaurant Ratner’s, the Fillmore East seated about 2,700 people in a repurposed theater (more later about the history of that theatre). Tickets were an affordable $3.50 to $5.50, which allowed me to sit just a few rows from the stage and witness some of the greatest performances of the era. The Fillmore East hosted a dazzling array of groundbreaking artists across genres. Note: As I write the following, I shake my head in amazement.

During those years, from the stage of the Fillmore, I was witness to performances by Jimi Hendrix, Cream with Eric Clapton, Quicksilver Messenger Service, Steve Miller, The Who (premiering Tommy), Procol Harum, The Electric Flag, B.B. King, Chuck Berry, Albert King, Jefferson Airplane, Pink Floyd, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, Traffic with Stevie Winwood, Janis Joplin, Joe Cocker, Johnny Winter, Neil Young and Crazy Horse, Richie Havens, Sam & Dave, Wilson Pickett, Vanilla Fudge, King Crimson, and Miles Davis.

What a time to be alive—learning, exploring, and being part of a transformative cultural moment, all set to the soundtrack of some of the greatest music ever made.

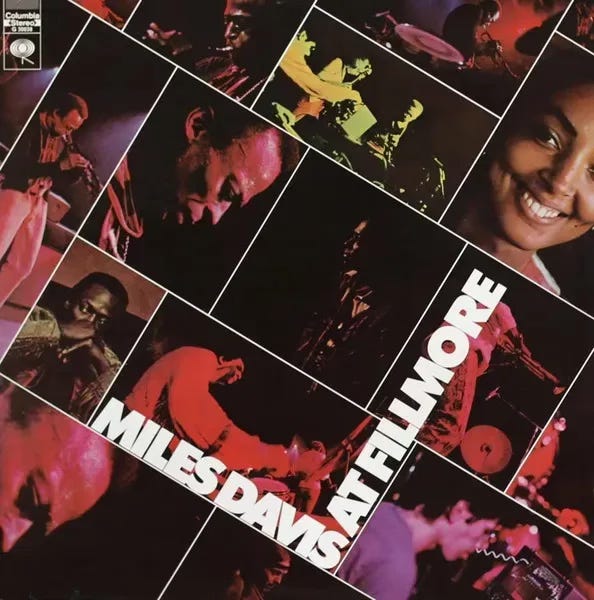

I was lucky enough to be present for both of Miles Davis’ appearances at the Fillmore East in 1970. Both concerts were recorded and remain available on Columbia Records. The first, in March, was a historic moment as it marked Wayne Shorter’s last gig with the band, which also featured Chick Corea on electric piano, Dave Holland on bass, and Jack DeJohnette on drums. Jazz was evolving at lightning speed back then. Miles had already released In a Silent Way and Bitches Brew, two groundbreaking albums that reshaped music. His innovations inspired an entire wave of new groups, including The Headhunters, Mahavishnu Orchestra, Return to Forever, Weather Report, and the Tony Williams Lifetime. These artists—Miles, Herbie Hancock, Chick Corea, Joe Zawinul, Tony Williams, and John McLaughlin—were transforming America’s classical music, creating a new jazz fusion movement that, like all innovations, had its supporters and detractors. I loved it all and felt incredibly fortunate to witness these transformative performances in New York.

The second Miles concert, just a few months later, was a four-night run that was eventually released as Miles at Fillmore. This show completely blew my mind. Miles shared the bill with Laura Nyro, the brilliant singer-songwriter and pianist known for her poetic, genre-blending music.

Miles being Miles, of course, had to open the show—the man wasn’t about to sit around listening to anyone else play. The second his set wrapped, he was out the door, probably before the applause even died down.

One night, during Miles’ electric, brain-melting eras, Marguerite Eskridge—his girlfriend at the time—hopped into my cab. The second she slid into the seat, I understood exactly why Miles was always in such a hurry to get home. Marguerite wasn’t just beautiful; she was a presence, like she carried a piece of that otherworldly energy Miles had. You didn’t just look at her—you felt her. And for a man like Miles, who lived for intensity, for that edge-of-the-cliff feeling, she must’ve been like gravity.

I knew Miles had made some changes to his group, but I wasn’t prepared for what I saw when the curtain went up. Chick, Holland, and DeJohnette were on stage, joined by Steve Grossman on saxophones and Airto Moreira on percussion. Then came the big surprise—Keith Jarrett appeared, playing a Farfisa electric organ. With Keith on one side of the stage and Chick on the other, the sound was electrifying. The music was unlike anything I’d ever heard, keeping me on the edge of my seat throughout the set. I was so overwhelmed that I left after Miles’ performance, unable to imagine anything that could follow it. Looking back, I regret missing Laura Nyro, who tragically passed away far too soon from ovarian cancer.

Graham’s influence stretched beyond just music. His Fillmore venues became symbols of unity and freedom, where people gathered to experience the revolution happening in music and culture. The Fillmore East, located in the heart of Manhattan’s East Village, wasn’t just a venue—it was a space where the social and political energy of the 60s could be felt in every note played. In much the same way, the Fillmore West in San Francisco became a cornerstone of the Bay Area’s rich musical legacy, from its bohemian culture to its vibrant music scene that defined the era.

The building itself had a fascinating history. Built in 1922 by Jewish entrepreneurs Elias Meyer and Louis Schneider, it began as the Commodore, a Yiddish theater that became a cultural cornerstone for the immigrant Jewish community. In the 20s, Yiddish Theaters lined Second Avenue from 14th to Houston Street. Stars like Paul Muni, Edward G. Robinson, Lee Strasberg, and Walter Matthau honed their craft in the Yiddish theater, creating a legacy that extended into Hollywood and Broadway. Billy Crystal’s family also had ties to the venue—his uncle Milt Gabler, of Commodore Records, hosted jam sessions there in the 50s. Crystal later recalled in his show 700 Sundays how Billie Holiday babysat him while his family worked at the theater.

By the 1960s, the venue became the Village Theatre, hosting everything from Timothy Leary’s lectures to avant-garde jazz concerts. A memorable 1966 double bill organized by George Wein featured separate sets by John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman, pioneers of free jazz. In 1967, I saw the Charles Lloyd Quartet perform there, with Keith Jarrett and Jack DeJohnette, both in their mid-20s and already brilliant.

Among all the incredible music I heard at the Fillmore East, two groups stand out as enduring favorites—Procol Harum and the Electric Flag. Half a century has passed and I still find myself returning to their timeless music, a reminder of just how exciting it was to be in the third row at the Fillmore East..

Most people peg Procol Harum as the band that gave us “A Whiter Shade of Pale”—that swirling, trippy fusion of rock, baroque vibes, and soul that basically defined 1967’s Summer of Love. Sure, it sold five million copies and put the band on the map, but Procol Harum wasn’t just about Bach riffs and poetic riddles. The next year, they recorded, In Held Twas In I, a beast of a track—eighteen minutes long, mind you—dropped on their second album, Shine On Brightly, and it wasn’t just a song. It was a full-on musical odyssey. Five interconnected sections, blending everything from spoken word to instrumental freakouts to straight-up existential crises. This wasn’t radio candy; it was a deep dive into the human condition. The opening, Glimpses of Nirvana, doesn’t hold your hand—it throws you headfirst into a contemplative swamp of Eastern philosophy and life’s big, unanswerable questions.

This was the soundtrack to a soul-searching acid trip. Spiritual yearning, inner demons, and the whole why-are-we-here thing, all set to music that tore up the traditional pop and rock playbook. It wasn’t just a song; it was an experience, a dare for listeners to go deeper.

Even now, “In Held ’Twas in I” stands tall, a monument to the era’s experimental spirit. It bridges rock and classical like it’s the most natural thing in the world, daring anyone listening to dream bigger. It’s a bold, fearless, high-wire act of creativity that screamed, “Rock music doesn’t have to stay in its lane.”

Procol Harum broke the rules, rewrote the script, and left a blueprint for what rock could become. “In Held ’Twas in I,” with lyrics by Keith Reid and music by Gary Brooker and Matthew Fischer, wasn’t just ahead of its time; it was out of time, a landmark for anyone brave enough to follow.

Mike Bloomfield, playing with The Electric Flag at the Fillmore East, was one of the most electrifying guitarists I ever heard—a trailblazer who fused blues, rock, and jazz into a style that was both groundbreaking and deeply soulful. Rooted in the blues tradition and shaped by legends like Muddy Waters and B.B. King, Bloomfield’s playing combined emotional intensity, technical brilliance, and a knack for improvisation that pushed boundaries and redefined electric blues. The Electric Flag itself was revolutionary, blending blues, rock, soul, and jazz with a horn section to create a bold, genre-defying sound that paved the way for horn-driven rock bands like Chicago and Blood, Sweat & Tears, leaving an indelible mark on an era of musical innovation.

Thirty years later, while living in Tucson, I met Harvey Brooks, the bassist for The Electric Flag, who living in the Arizona desert at the time, and we became friends. Harvey’s remarkable career included playing on Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew, collaborating with Jimi Hendrix and The Doors, and being part of the band that backed Bob Dylan—alongside Mike Bloomfield—at the legendary and controversial August 28, 1965, concert at Forest Hills Tennis Stadium. That performance marked the beginning of Dylan’s first electric tour, which shook the folk music world.

I even had the privilege of creating a video with Harvey about The Electric Flag:

Today, Harvey and his wife, Bonnie, reside in Jerusalem. And I’ve relocated to Mexico. We both have managed to live, happily after ever. However, some of our greatest memories are the music from that magic era, when all seemed possible and sometimes, it was, musically, at the Fillmore East.

Though the Fillmore East and West are no longer with us, their legacy endures. Bill Graham’s vision of combining music, community, and cultural revolution became the foundation for a golden age of live music that will never be replicated. The Fillmore East in New York, with its rich history of rock, jazz, and everything in between, continues to inspire the next generation of music lovers, while Graham’s imprint on both coasts remains a touchstone in the history of live performance.

Friday, The Saxophone Summit at Birdland, the historic 1999 webcast, which featured Michael Brecker, Joe Lovano and David Liebman.

Enjoy this week and don’t forget, let your conscience be your guide.

Thanks. Mysterious first and humane second. Just right for my ears and heart. Never into drugs, but like the trips.

Although it is in Portuguese, the musical selection is top quality. All recordings are live at Bill Graham's house.

https://dadaradio.net/fillmore/